Looking & Seeing

one long look at one work of art . . . or two or three

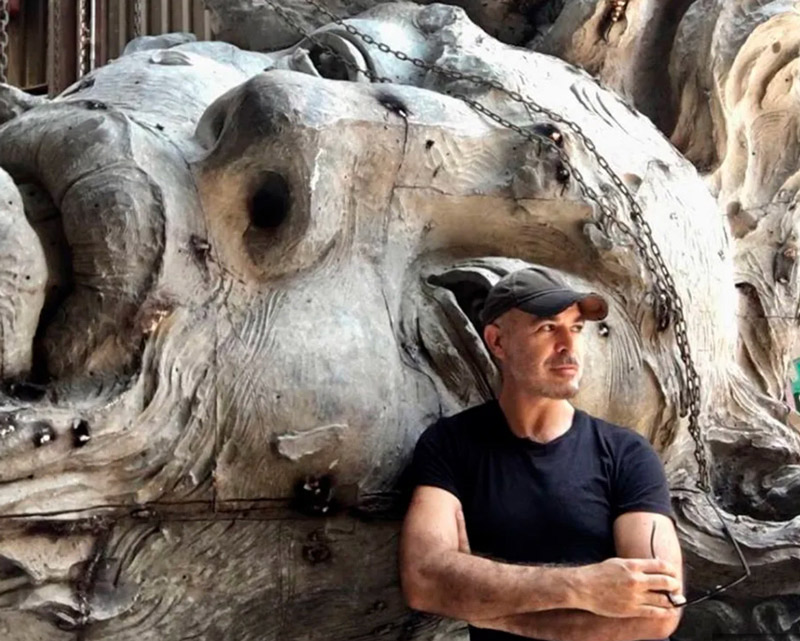

John O'Hern is an arts writer, curator and retired museum director who is providing a weekly contemplation of a single work of art from our gallery. In our fast-paced lives overflowing with information, we find it necessary and satisfying to slow down and take time to look. We hope you enjoy this perspective from John.

John O'Hern has been a writer for the 5 magazines of International Artist Publishing for nearly 20 years. He retired from a 35-year-long career in museum management and curation which began at the Albright-Knox Art Gallery where he was in charge of publications and public relations and concluded at the Arnot Art Museum where he was executive director and curator. At the Arnot Art Museum he curated the groundbreaking biennial exhibitions Re-presenting Representation. John was chair of the Visual Artists Panel of the New York State Council on the Arts and has written essays for international galleries and museums.

May 18, 2025

contemplations on a theme

Today's theme is Time

As Memorial Day approaches, I’ve been thinking about the observance of the day in the past—reciting the Gettysburg Address in front of the impressive Civil War Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Monument on the Lawson Common and playing in the Satuit Band in the Memorial Day Parade. (“Satuit” is the Wampanoag word for “Cold Brook” which runs behind what was my family home which, in an earlier time, was known as “Brookside Inn”. In 1640, Satuit was Anglicized to Scituate—for some, the unpronounceable name of a town on the South Shore of Boston.)

Memorial Day was the beginning of the summer tourist season which ended on Labor Day. My mother remembered that as a girl she had to wear her winter woolen underwear until that day no matter what and, I remember being warned not to go into the ocean any earlier than that.

All that remembering got me to the theme of “Time”. There’s a great quote about time attributed to Albert Einstein, Richard Feynman, Woody Allen and others: “Time is what keeps everything from happening at once.” Van Gogh wrote, “It is looking at things for a long time that ripens you and gives you a deeper meaning.” A good segue into this week’s theme for Looking and Seeing.

All that remembering got me to the theme of “Time”. There’s a great quote about time attributed to Albert Einstein, Richard Feynman, Woody Allen and others: “Time is what keeps everything from happening at once.” Van Gogh wrote, “It is looking at things for a long time that ripens you and gives you a deeper meaning.” A good segue into this week’s theme for Looking and Seeing.

In New England, the mountains, for the most part, have been softened by erosion and second growth trees after having been heavily forested beginning in the 17th century. (The lumber for Brookside Inn arrived in Scituate Harbor on a wooden schooner from Maine.)

The landscape of the Southwest is different. Its history is revealed in exposed rock.

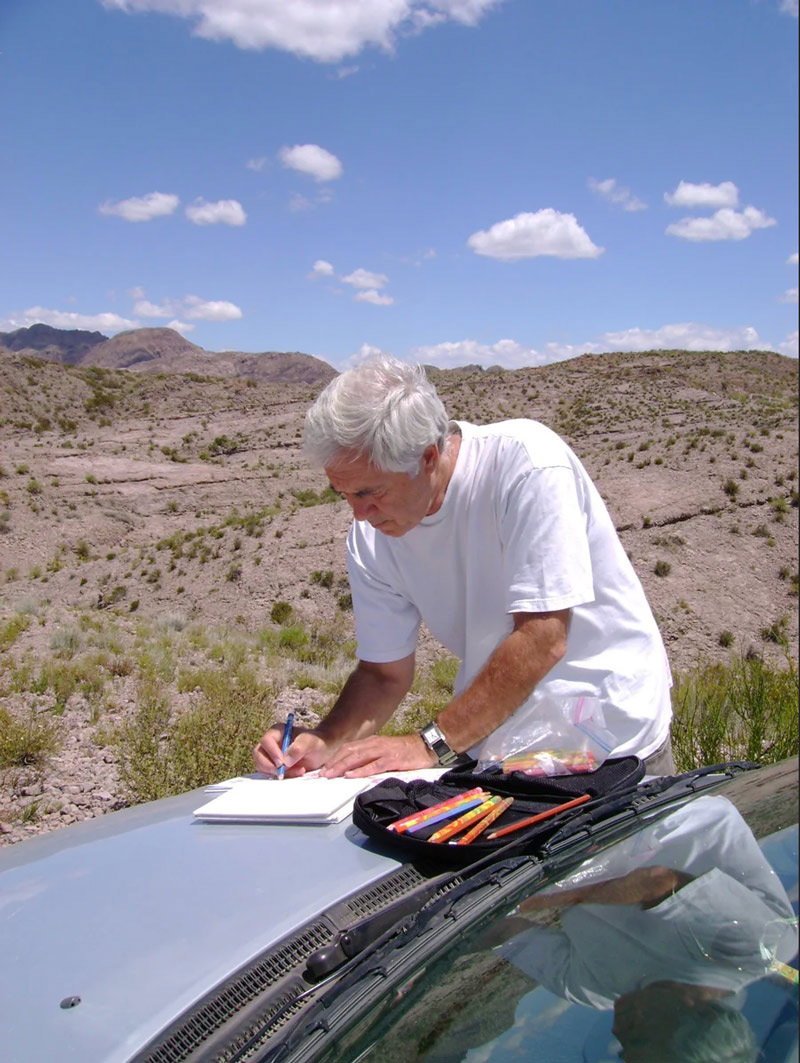

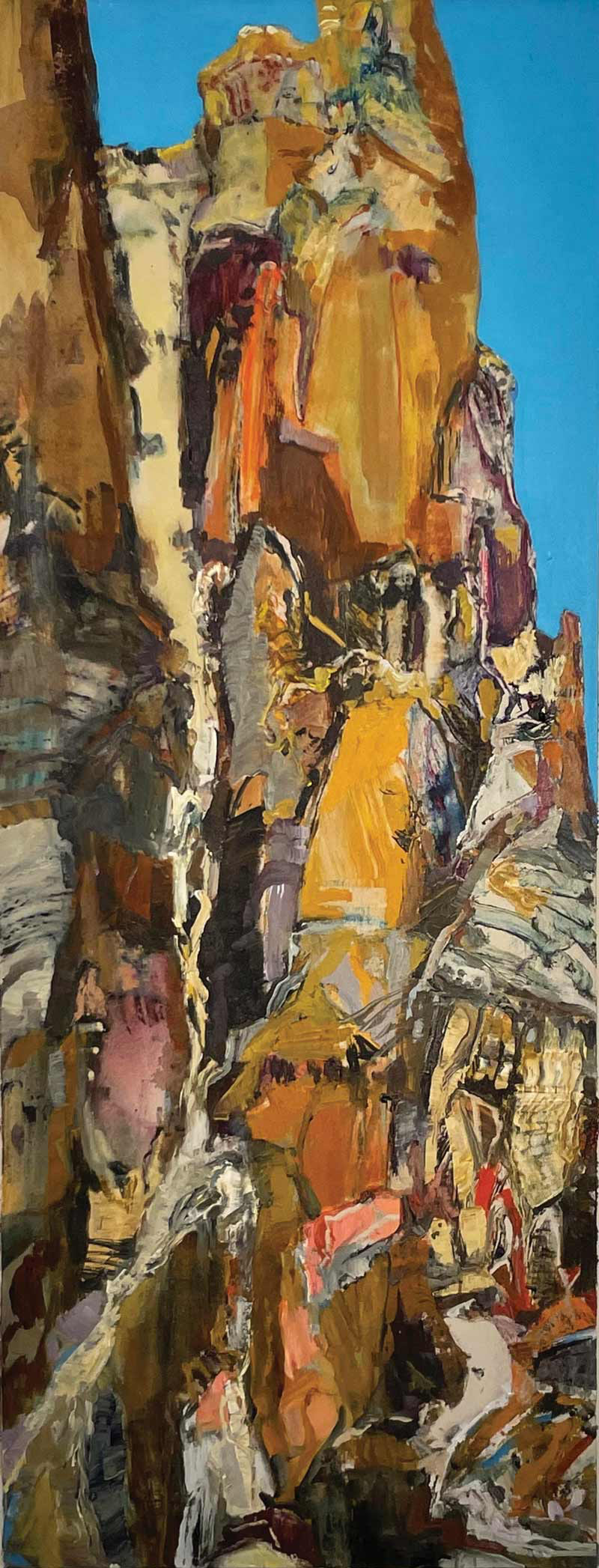

David T. Alexander’s Multicoloured Erosional Mountains is an impression of the geological formation of the mountains and their continuing erosion, their clear strata of formation eroding together in wind and rain, blurring their history over time. His paintings embody the erosive geologic process as he builds up paint with brushes and trowels.

David T. Alexander’s Multicoloured Erosional Mountains is an impression of the geological formation of the mountains and their continuing erosion, their clear strata of formation eroding together in wind and rain, blurring their history over time. His paintings embody the erosive geologic process as he builds up paint with brushes and trowels.

In her essay on David’s work in the 2024 edition of Evokation, Staci Golar quotes his impressions of the processes of nature. ‘When it rains in the desert, the top layer of pigment in the soil gets washed down and runs over the other colors by gravity, like a brush veil of color from the top distributes the color to the bottom . . .That’s a thrill . . . and it’s not just the way it looks, but the way it feels in my experience . . . Things such as the crust of a hot land’s pigment are like colors of chiles, maize in unique shapes created by erosion. These things are what helped me create images of a land in flux.”

Esha Chiocchio’s drone photographs of the parched Lordsburg Playa in southern New Mexico, depict a land in flux and the intense effort to rejuvenate it. She writes, “In the late 1880s, when Euro-American settlers founded Lordsburg along the Southern Pacific Railroad line in the southwest corner of New Mexico, a sea of grass tickled their horses' bellies and provided ample feed for their growing herds of livestock. Yet, within a century, cattle had eaten the grass to the ground, and dust storms frequently enveloped Interstate 10, causing over forty fatalities along a twenty-mile stretch of highway since 1965.” She has been documenting the revitalization of the Playa for several years.

Esha Chiocchio’s drone photographs of the parched Lordsburg Playa in southern New Mexico, depict a land in flux and the intense effort to rejuvenate it. She writes, “In the late 1880s, when Euro-American settlers founded Lordsburg along the Southern Pacific Railroad line in the southwest corner of New Mexico, a sea of grass tickled their horses' bellies and provided ample feed for their growing herds of livestock. Yet, within a century, cattle had eaten the grass to the ground, and dust storms frequently enveloped Interstate 10, causing over forty fatalities along a twenty-mile stretch of highway since 1965.” She has been documenting the revitalization of the Playa for several years.

In an earlier edition of Looking and Seeing I commented on her photograph, Morning Train. The distant train, to me, appeared like a zipper across the 40-inch-wide image. Unzip the lower part of the photo of the Playa and substitute the arid desert, and you have images of a time of drought and a time of replenishment. Esha commented, “The train image needs to be large to be read properly. I got up early and went out to see what was going on. There was fog that morning and a train was passing in the distance. It was trains that opened up the land for ranchers and allowed them to get their cattle out to market. Heavy grazing consequently caused the grasslands to virtually disappear.”

Jeremy Miranda’s painting Middle of March depicts a lengthy moment in what we called, when I lived in Maine, mud season. Another description of Maine weather is that there are two season, winter and the fourth of July. In experience, Maine seasons are varied and beautiful. In Middle of March, mountain snows and frozen ground are melting and streams are coming back to life, the browns just beginning to give way to myriad greens.

Jeremy Miranda’s painting Middle of March depicts a lengthy moment in what we called, when I lived in Maine, mud season. Another description of Maine weather is that there are two season, winter and the fourth of July. In experience, Maine seasons are varied and beautiful. In Middle of March, mountain snows and frozen ground are melting and streams are coming back to life, the browns just beginning to give way to myriad greens.

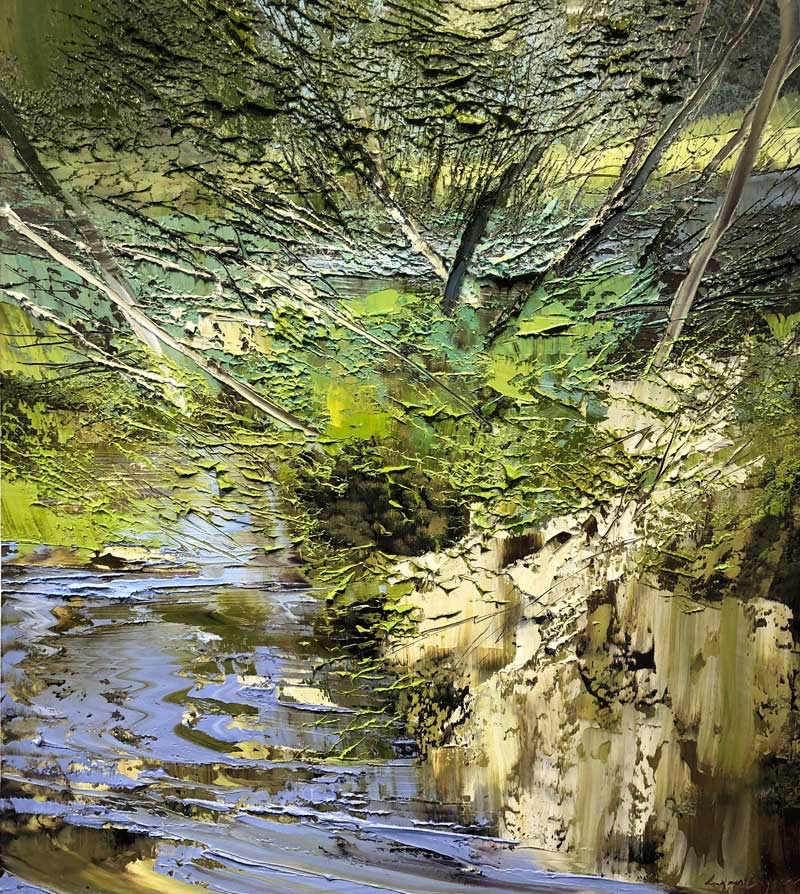

In a recent painting Creek Light, lush with greens, Jeremy noted, “The creek really woke up this week!” His paintings are alive with the subtleties of light from that of a gas flame on his kitchen stove to sunlight on a houseplant, to the shimmering reflections on a forest creek.

In a recent painting Creek Light, lush with greens, Jeremy noted, “The creek really woke up this week!” His paintings are alive with the subtleties of light from that of a gas flame on his kitchen stove to sunlight on a houseplant, to the shimmering reflections on a forest creek.

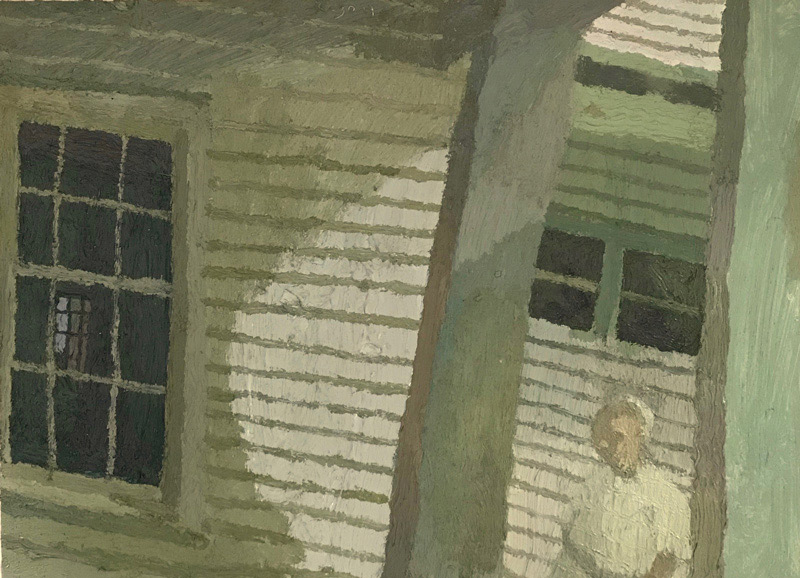

Rowan Oak was William Faulkner’s home in Oxford, MS, for 32 years. He and his wife restored the decaying antebellum Greek Revival home. Also on the property is a barn which was built in the 1840s probably as the home of the original owners while the larger home was being built. The property is owned by the University of Mississippi, where Brian Rego is a visiting faculty member this year. Faulkner’s Cabin is one of several observations of the property he has done over the years.

Rowan Oak was William Faulkner’s home in Oxford, MS, for 32 years. He and his wife restored the decaying antebellum Greek Revival home. Also on the property is a barn which was built in the 1840s probably as the home of the original owners while the larger home was being built. The property is owned by the University of Mississippi, where Brian Rego is a visiting faculty member this year. Faulkner’s Cabin is one of several observations of the property he has done over the years.

In 2014, I interviewed Brian when he had co-founded a painting collective known as Perceptual Painters that emphasized painting, community and education. The painters rely on direct observation, painting their response to what is in front of them. He commented, then, on the energy that comes “from working directly from the motif.”

In an early edition of Looking and Seeing, Brian spoke about nature. “On a physical level, we come from it, and we return to it. There’s beauty and unpredictability, order and disorder, deconstruction and reconstruction. There’s the intelligence of nature. There are visual phenomena and those that can be described by physics, and there is the metaphysical. I sense all that happening at once. It’s profound, both present and timeless. It’s the miracle of existing, the fact that it even exists and even seems to exist beyond itself.”

Aron Wiesenfeld’s subjects exist in a physical and metaphysical world, possessed of an inner strength or awareness that allows them to navigate an often hostile landscape on a journey they may not understand the purpose of until they reach its end. His paintings also attract us to accompany them on their journeys or on our own.

Aron Wiesenfeld’s subjects exist in a physical and metaphysical world, possessed of an inner strength or awareness that allows them to navigate an often hostile landscape on a journey they may not understand the purpose of until they reach its end. His paintings also attract us to accompany them on their journeys or on our own.

The Handmaid appears to beckon us to follow her into a tunnel. Tunnels and openings appear often in his work, “A loaded symbol” he says, a journey “between one reality and another”. Her mysterious presence is irresistible. We will join her, not knowing the purpose of the journey or the destination but, perhaps, feel the journey will take us to a more expansive, fulfilling realm—a different time. When we first spoke over 9 years ago, Aron commented on the mysterious paintings of Edward Hopper. “Most people see his paintings as materialistic with a beautiful light. I look at Hopper and see the metaphysical.”

Time is, as Brian Rego says, all “happening at once”—a mind-boggling concept that has occupied philosophers and scientists for hundreds of years. Emily Dickinson, who wrote her thoughts on scraps of paper and stashed them in the draw of her writing table, summed it up deceptively simply. In her poem “Forever”, she wrote, “Forever—is composed of nows."

May 4, 2025

contemplations on a theme

Today's theme is Only Connect.

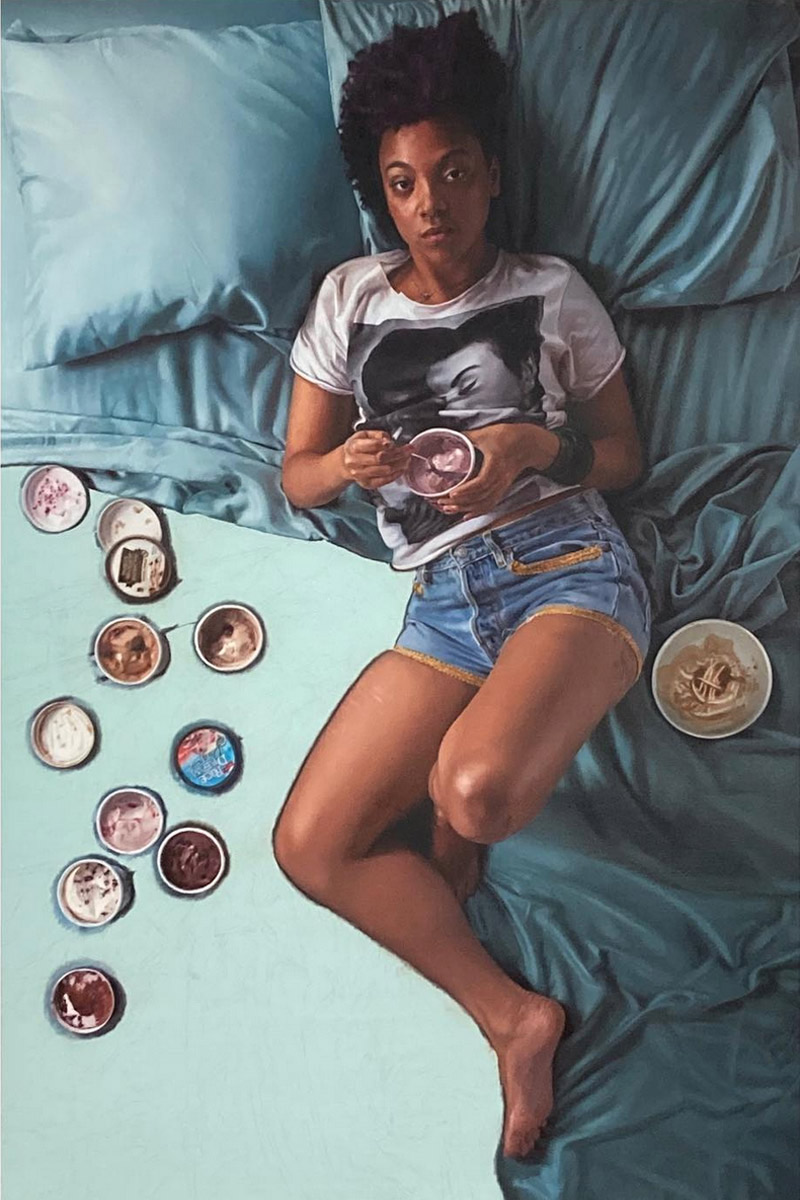

A number of words came up in conversation this week as possible themes for today’s episode. “Community” came up as gallerist Susan Guevera and I toured Lee Price’s stunning exhibition at the gallery—Lee’s earlier paintings featured her binge-eating alone and the new paintings depict her in groups or the detritus of a party. “Community” got me thinking about the etymology of a number of words in the same vein with the Latin prefix “com-“ or “con-“ meaning “together” or “with”. (Years of studying Latin. . . )

“Connect”, for a little more pedantry, comes from the Latin connectere, from con- ‘together’ + nectere ‘bind’. “Only connect” is the epigraph to E.M. Forster’s novel Howard’s End, referring both to connecting the parts of one’s self and connecting with others. It’s a quote I use far too often, but one that works in many contexts (from the Latin “weave together”!).

Lee’s painting Winter is an example of people having come together, celebrated and gone on. She says, “I would like people to have a sense of time passing. . . how transient life is.” The round table on the Asian rug recalls a mandala, a circular design with symbols often used to focus the mind in the meditative practices of Buddhism and Hinduism.

The plates and cups in Lee’s painting say something about each of the people who shared in the party—some didn’t finish and some couldn’t get enough, scooping up the remaining frosting with their fingers. Three left their napkins on the table (one with a smudge of chocolate) and one left it on the chair. The once carefully-laid table is now disordered, the table cloth crumbled and stained. The acts of living sometimes mess things up.

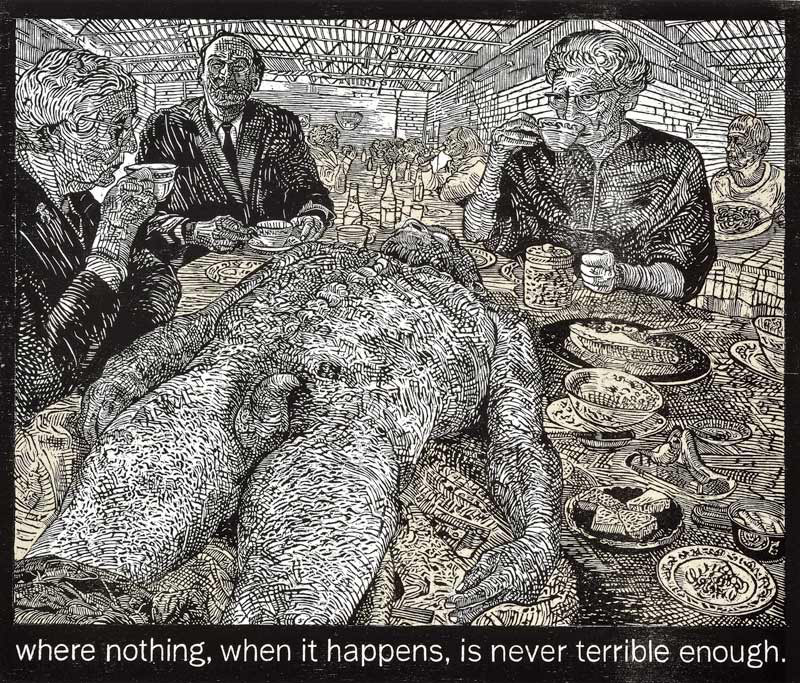

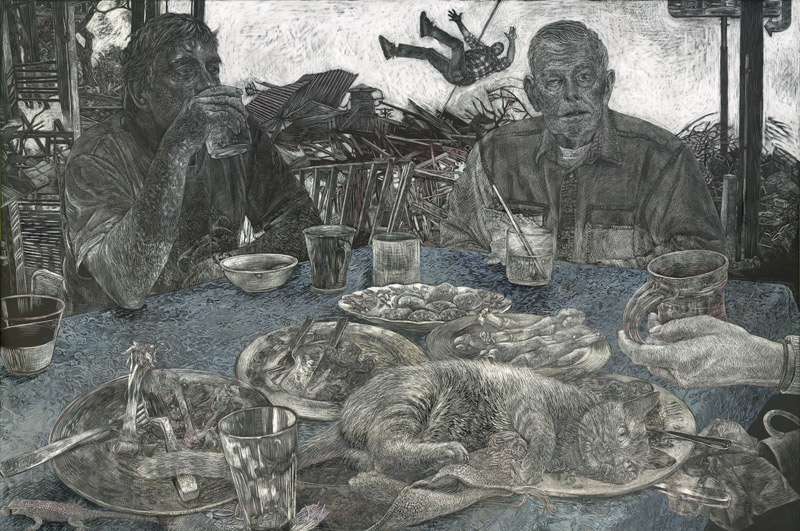

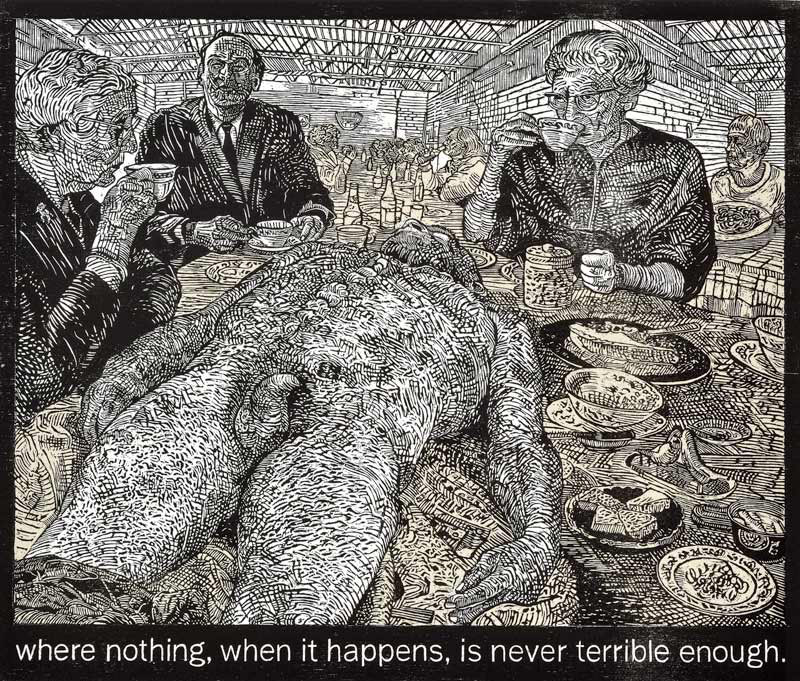

In another table setting, Alice Leora Briggs’ woodcut Where nothing, when it happens is never terrible enough, there is no connection. Two genteel ladies and a gentleman sip tea oblivious to the party behind them and to the corpse lying on the table in front of them. Decorum often demands ignoring the elephant (or the corpse) in the room or connecting at all.

In another table setting, Alice Leora Briggs’ woodcut Where nothing, when it happens is never terrible enough, there is no connection. Two genteel ladies and a gentleman sip tea oblivious to the party behind them and to the corpse lying on the table in front of them. Decorum often demands ignoring the elephant (or the corpse) in the room or connecting at all.

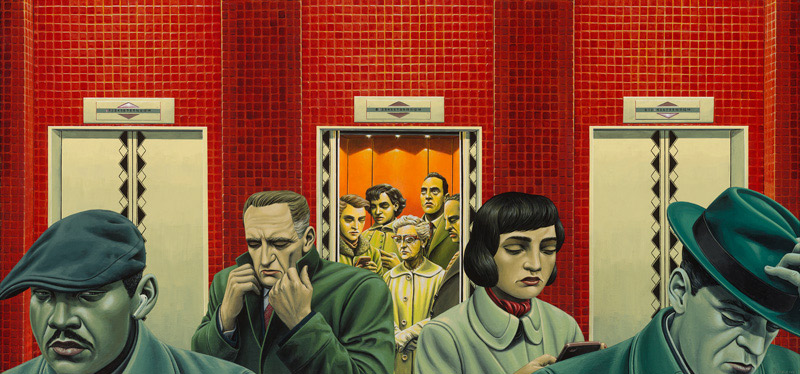

Gregory Ferrand writes, “My most recent work explores the feeling and reality of being disconnected and alienated (which results in multiple personal realities), despite and sometimes because of the proximity in which we live to one and other.” In I Am Not Really Here, he reflects on our all being the same but different. “…it is incumbent upon us to reflect on how the realities we construct make us different and also how, by just being human, we are the same.” People cramped physically in the elevator quickly disperse on their separate ways. As Rudyard Kipling said, “never the twain shall meet.”

Gregory Ferrand writes, “My most recent work explores the feeling and reality of being disconnected and alienated (which results in multiple personal realities), despite and sometimes because of the proximity in which we live to one and other.” In I Am Not Really Here, he reflects on our all being the same but different. “…it is incumbent upon us to reflect on how the realities we construct make us different and also how, by just being human, we are the same.” People cramped physically in the elevator quickly disperse on their separate ways. As Rudyard Kipling said, “never the twain shall meet.”

There are communities that connect, however. The rich cultural and religious heritage in Northern New Mexico of the Spanish settlers who first arrived in 1598, is still alive today. The Feast of Our Lady of Guadalupe is a time of coming together and of celebrating. When Our Lady appeared to the peasant Juan Diego, she communicated with him in his native language and told him to go to the archbishop of Mexico City requesting he build a church on the site of her visitation. The archbishop was dubious and asked for a sign. Our Lady told Juan Diego to gather roses, although it was December. She put the roses in Juan Diego’s cloak and sent him to the archbishop. When Juan Diego opened his cloak, the roses tumbled to the floor and an image of Our Lady appeared on the fabric.

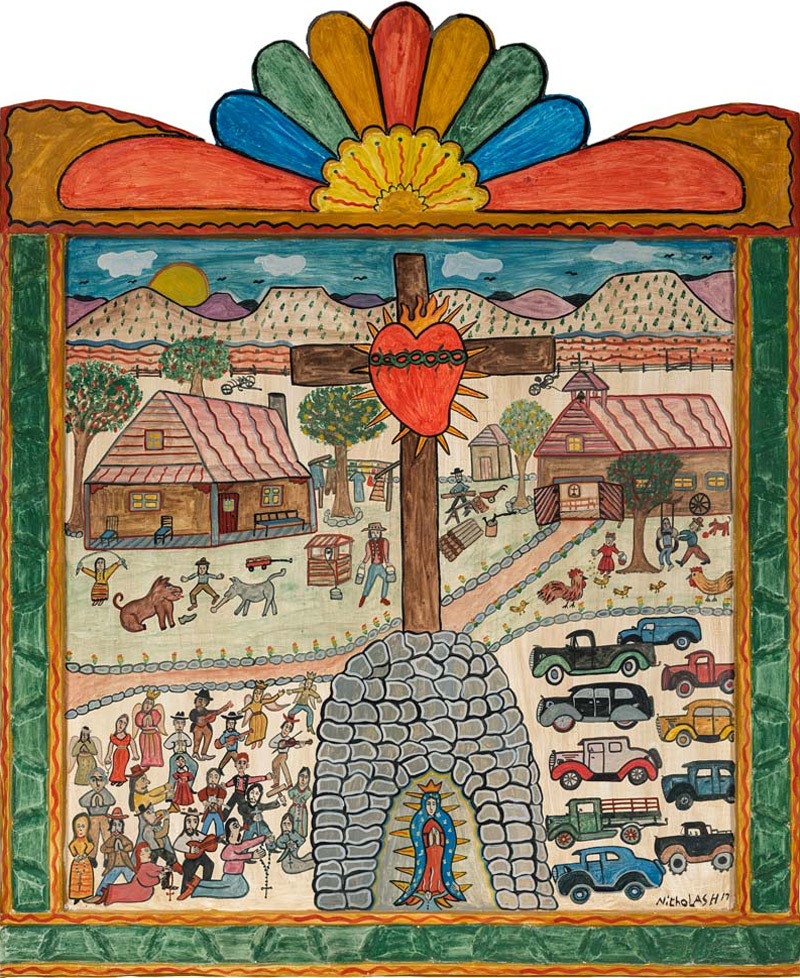

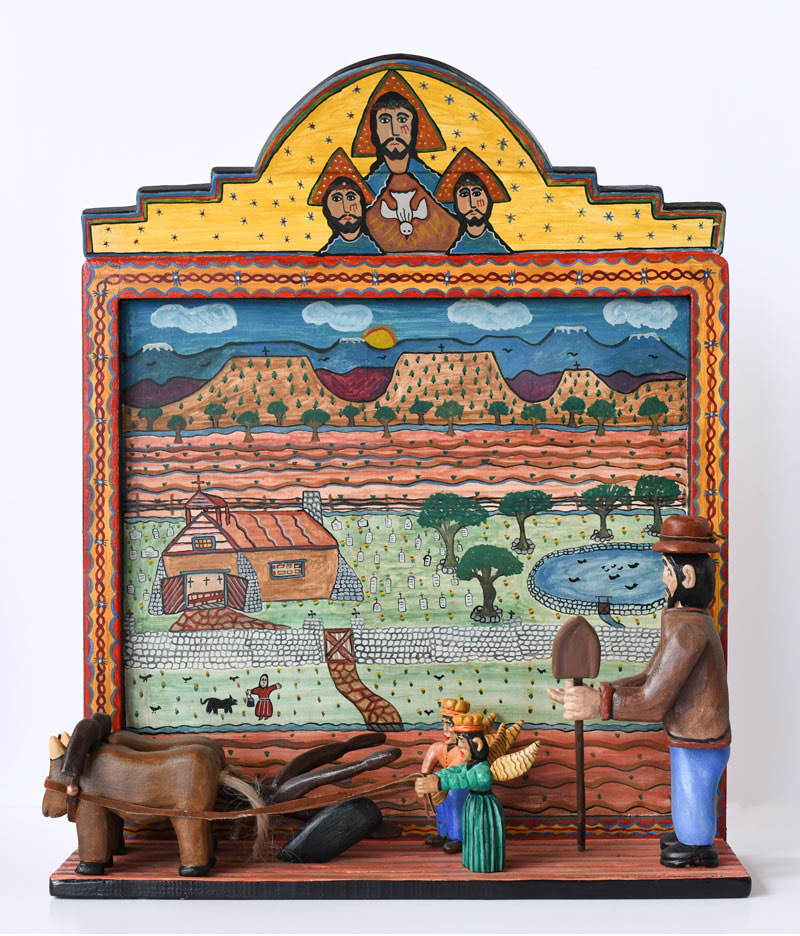

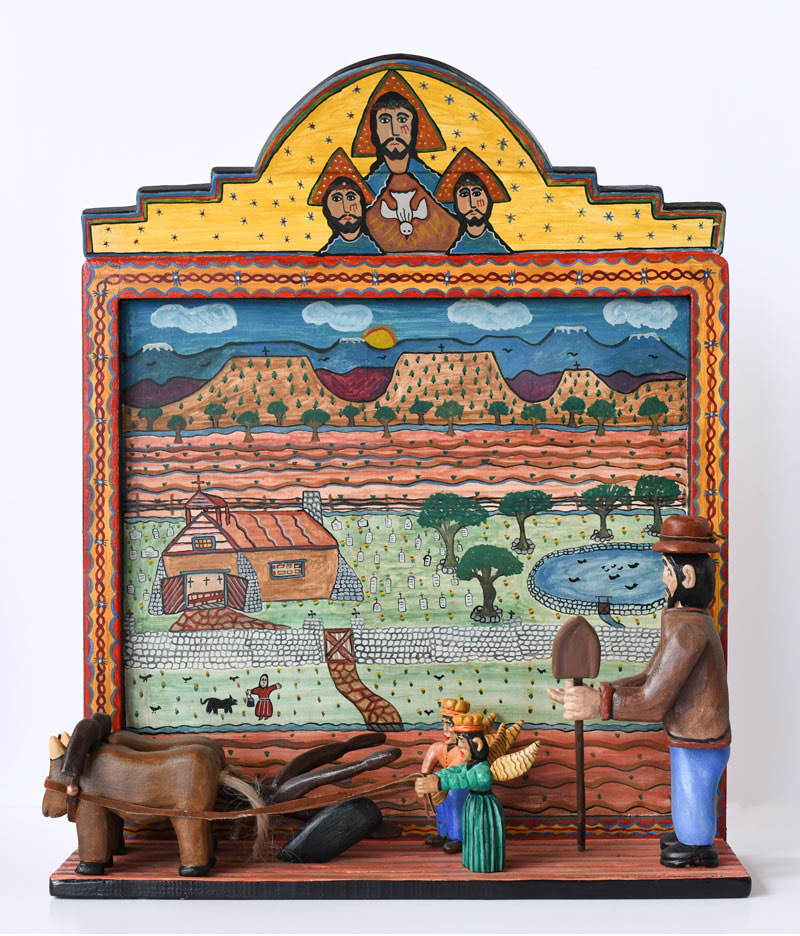

Nicholas Herrera, the El Rito Santero, carved and painted Dia de la Virgen de Guadalupe, depicting the Virgin in her shrine and a gathering of people worshipping and celebrating. Behind the shrine is a scene of people contributing to the daily life on a farm—sawing wood, feeding the chickens, gathering water from the well, and children playing with animals. BTW (The past participle of the Latin verb contribuere, “to bring together”.)

Nicholas Herrera, the El Rito Santero, carved and painted Dia de la Virgen de Guadalupe, depicting the Virgin in her shrine and a gathering of people worshipping and celebrating. Behind the shrine is a scene of people contributing to the daily life on a farm—sawing wood, feeding the chickens, gathering water from the well, and children playing with animals. BTW (The past participle of the Latin verb contribuere, “to bring together”.)

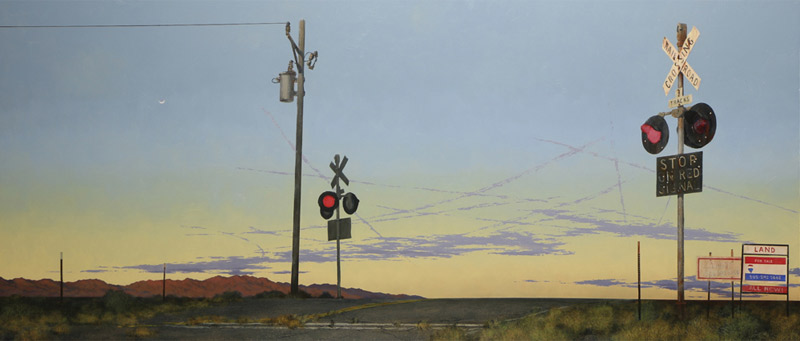

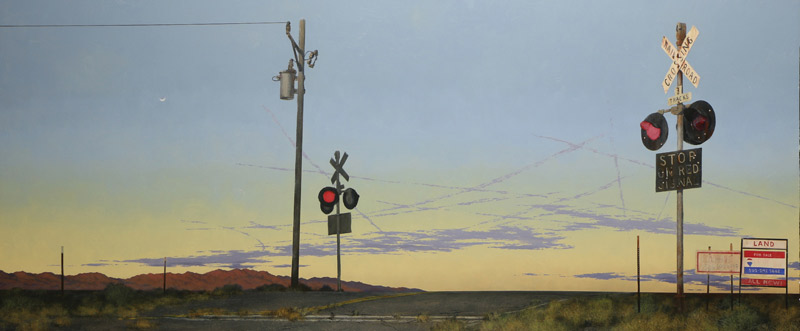

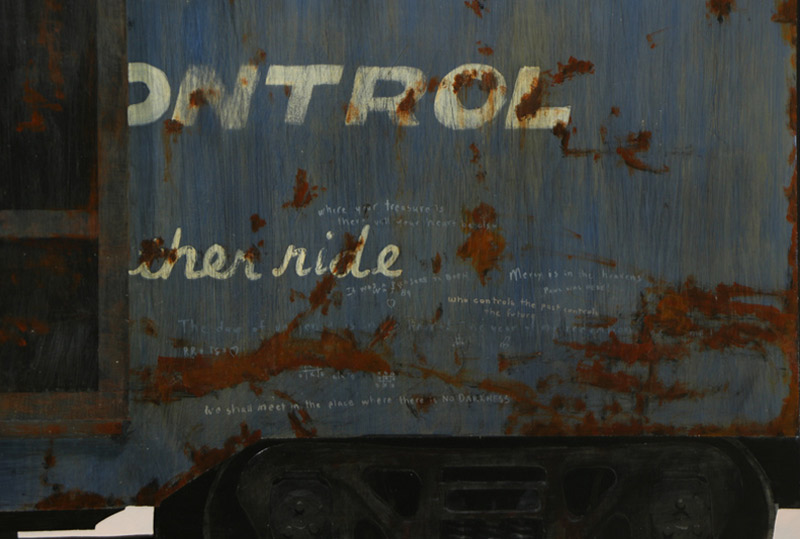

In Francis DiFronzo’s Crossing Paths, Part 2, communication takes place through signs—flashing red lights warn drivers to stop to let a train pass, and billboards advertise land for sale with a phone number to connect with the realtor. Contrails of passenger-filled planes cross in the sky connecting people between cities.

In Francis DiFronzo’s Crossing Paths, Part 2, communication takes place through signs—flashing red lights warn drivers to stop to let a train pass, and billboards advertise land for sale with a phone number to connect with the realtor. Contrails of passenger-filled planes cross in the sky connecting people between cities.

The connection between humans and animals was summed up by Henry Beston in his book “The Outermost House”—a favorite book and a favorite place to visit before the house was swept out to sea. He wrote, “The animal shall not be measured by man. In a world older and more complete than ours, they move finished and complete, gifted with extension of the senses we have lost or never attained, living by voices we shall never hear. They are not brethren; they are not underlings; they are other nations, caught with ourselves in the net of life and time, fellow prisoners of the splendor and travail of the earth.”

The connection between humans and animals was summed up by Henry Beston in his book “The Outermost House”—a favorite book and a favorite place to visit before the house was swept out to sea. He wrote, “The animal shall not be measured by man. In a world older and more complete than ours, they move finished and complete, gifted with extension of the senses we have lost or never attained, living by voices we shall never hear. They are not brethren; they are not underlings; they are other nations, caught with ourselves in the net of life and time, fellow prisoners of the splendor and travail of the earth.”

The connection and flow of energy between a bird and a woman is beautifully realized in Kristine Poole’s sculpture Duende. I quoted Kristine in an earlier edition of “Looking and Seeing”.

She has written, "Duende is a quality of passion and inspiration. This sculpture is about following your passion in life, represented by the bird, a Brahminy Kite. The design work on the bird's chest flows onto the woman's arm and continues across her back, highlighting the connection and communication between them. It also embodies the blossoming that occurs when passion is your guide through life. “The Brahminy Kite is often associated with Garuda, a powerful Hindu protector having the power to fly anywhere. The word Garuda has its origins in the verb "gri" - to speak. An important aspect of being guided by passion and inspiration is the ability to speak to yourself and others what is true for you. This opens the door to the unique path that is yours alone to wander. “Adding another level of meaning, her right hand that the Kite rests on is in the "Palli Mudra" --a hand symbol that represents listening to your inner voice and having confidence in yourself.”

We are learning more and more about physical connections in nature—and entanglement in quantum physics in which particles are connected despite being separated physically by great distances--a phenomenon with which my brain struggles to connect.

We are learning more and more about physical connections in nature—and entanglement in quantum physics in which particles are connected despite being separated physically by great distances--a phenomenon with which my brain struggles to connect.

Michael Scott’s Old Growth Forest is rich with connections that take place in the Olympic rain forest in Washington State. Trees grow and die, returning their nutrients to the soil. While living, the trees communicate via fungi in the soil called mycorrhizal networks and through the air by chemical signals, like pheromones. The interconnected flora of the forest connect with us on a different level. Michael writes, “Evening Light passing through a mature forest is an irresistible birth of color and a special chapter within a moment. These moments like droplets of moisture extend and expand us. The human mind has claimed this damp forest floor a pillow for the soul.”

In her book, “Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and the Teachings of Plants”, Robin Wall Kimmerer (Potawatomi) writes, “The trees act not as individuals, but somehow as a collective. Exactly how they do this, we don’t yet know. But what we see is the power of unity. What happens to one happens to us all. We can starve together or feast together.”

April 6, 2025

contemplations on a theme

Today's theme is the color blue.

On the first morning of the first day of my first trip to Ireland I went on a wildflower walk in the Burren in County Clare with a group of botanists and nature enthusiasts. One of the botanical curiosities of the Burren is that Mediterranean and Alpine wildflowers bloom together in the rocky terrain. I was looking for spring gentian which I mistakenly thought was the only true blue in nature. It isn’t. We saw one tiny plant on our walk.

The next day as I walked up a road past the grave of John O’Donahue, the poet, author, former priest and philosopher, I saw a group of people gathered at the side of the road. When I reached them, I saw they had found a large patch of spring gentian, one of them in the shape of a heart.

Among the songs that often sail through my head, and sometimes get stuck, is “Am I Blue?” I’m not sure if its Billie Holiday, Ray Charles or me singing, but it’s there. I’m seldom blue in the sense of The Blues, the musical form that came out of the African-American community in the deep south in the 1860s. The Blues is cathartic, though, when I am. B.B. King wrote, “Blues is a tonic for whatever ails you. I could play the blues and then not be blue anymore.”

I’ve been thinking about blue in art and the wonderful deep blue of lapis lazuli mined in what is now Afghanistan. The name comes from the Latin words “lapis”(stone) and “lazuli” which is derived from the Persian word for “blue” or “of the heavens--so, “stone of the heavens”.

I’ve been thinking about blue in art and the wonderful deep blue of lapis lazuli mined in what is now Afghanistan. The name comes from the Latin words “lapis”(stone) and “lazuli” which is derived from the Persian word for “blue” or “of the heavens--so, “stone of the heavens”.

The ancient Egyptians used lapis for the eyebrows and eye surrounds on the golden death mask of Tutankhamun. They also carved the stone as in the tiny Cult Image of the God Ptah now at The Met.

Later, lapis lazuli was ground into a powder and mixed with melted wax, oils, and pine resin and rinsed with other materials to create Ultramarine referring to its coming from “beyond the sea”. The material was rare and the process was time consuming and expensive. Michelangelo couldn’t afford it and Vermeer went into debt using it in his paintings.

Ultramarine was usually reserved for paintings of the blue mantle of the Virgin Mary. A spectacular example is The Virgin in Prayer, ca. 1654 by Giovanni Sassoferrato.

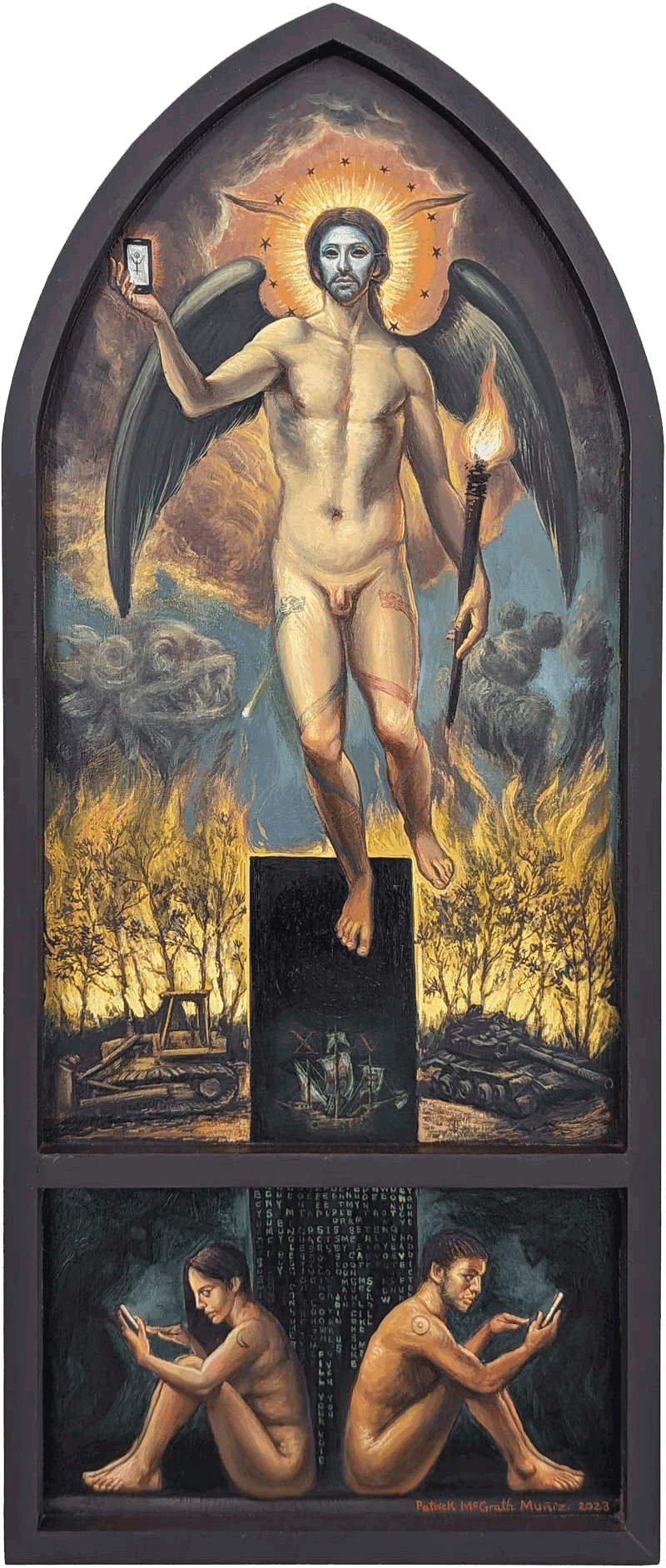

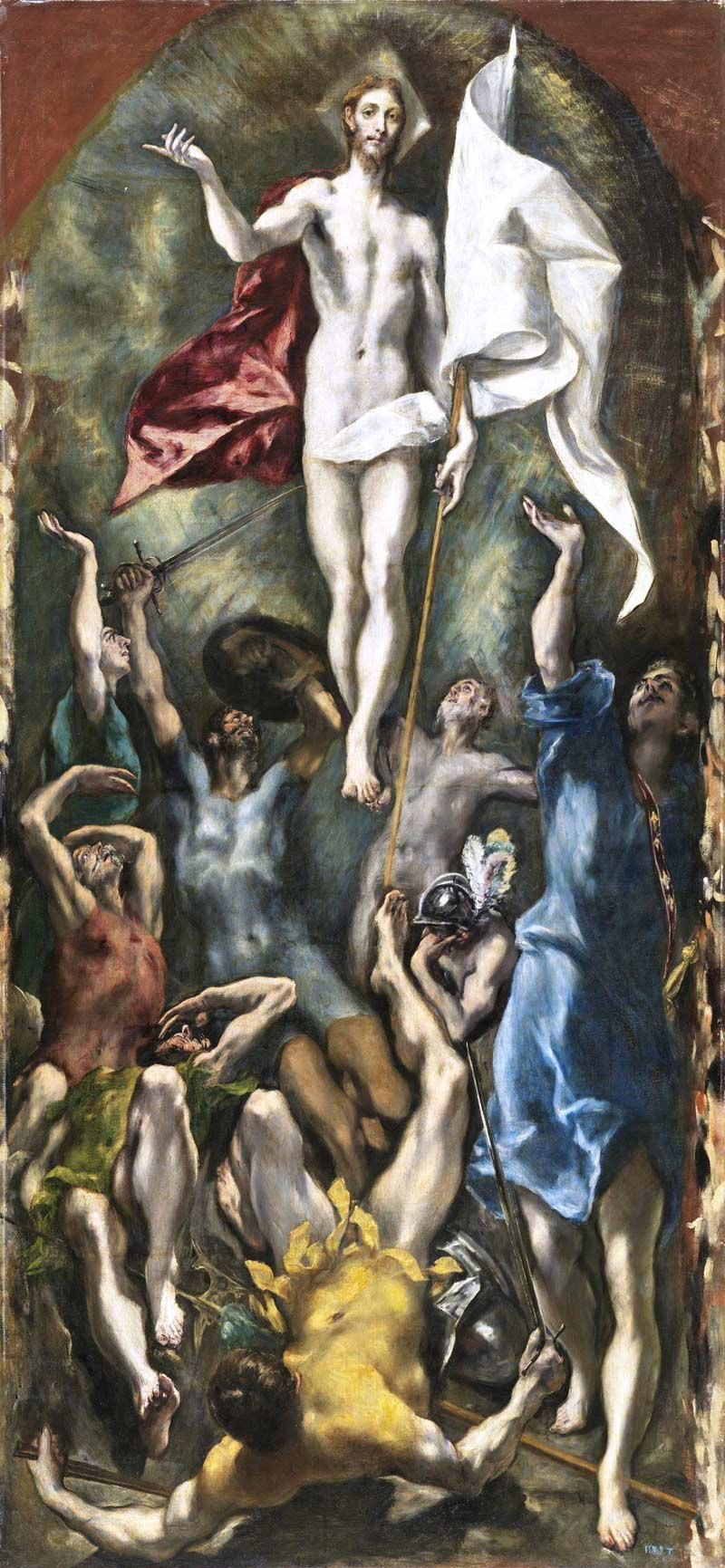

Patrick McGrath Muñíz painted his symbolically rich The Pale Blue Dot with the Virgin Mary draped in a deep blue mantle and about to hold Earth, a “pale blue dot” in her left hand. (For Patrick’s narrative on the painting, visit the Evoke website.)

Patrick McGrath Muñíz painted his symbolically rich The Pale Blue Dot with the Virgin Mary draped in a deep blue mantle and about to hold Earth, a “pale blue dot” in her left hand. (For Patrick’s narrative on the painting, visit the Evoke website.)

The “pale blue dot” appears in a photograph of Earth taken in 1990 by NASA's Voyager 1 spacecraft from a distance of nearly 4 billion miles. The astronomer Carl Sagan wrote, "Look again at that dot. That's here. That's home. That's us.”

The ultramarine of Sassoferrato and the deep blue of Patrick Muñíz are a reminder that blue isn’t just “blue”. We refer to the sea as blue but Homer referred to the “wine-dark sea”. (That’s another story all together and worth a journey down a rabbit hole.)

The poet Sylvia Plath wrote, “The sea was our main entertainment. When company came, we set them before it on rugs, with thermoses and sandwiches and colored umbrellas, as if the water - blue, green, gray, navy or silver as it might be - were enough to watch.”

Lynn Boggess painted the sea and its myriad colors on 20 July 2023. He says, “I want everything in a painting–full color, full texture, depth and space. It’s too darn easy to make paintings that are one thing.” In this painting there is not only the texture of the rocks but also the texture of the surface of the water as it flows and folds on itself, reflecting the stones and the sky. As light reflects off it and through it, the blue sea reveals itself to be more than that.

Lynn Boggess painted the sea and its myriad colors on 20 July 2023. He says, “I want everything in a painting–full color, full texture, depth and space. It’s too darn easy to make paintings that are one thing.” In this painting there is not only the texture of the rocks but also the texture of the surface of the water as it flows and folds on itself, reflecting the stones and the sky. As light reflects off it and through it, the blue sea reveals itself to be more than that.

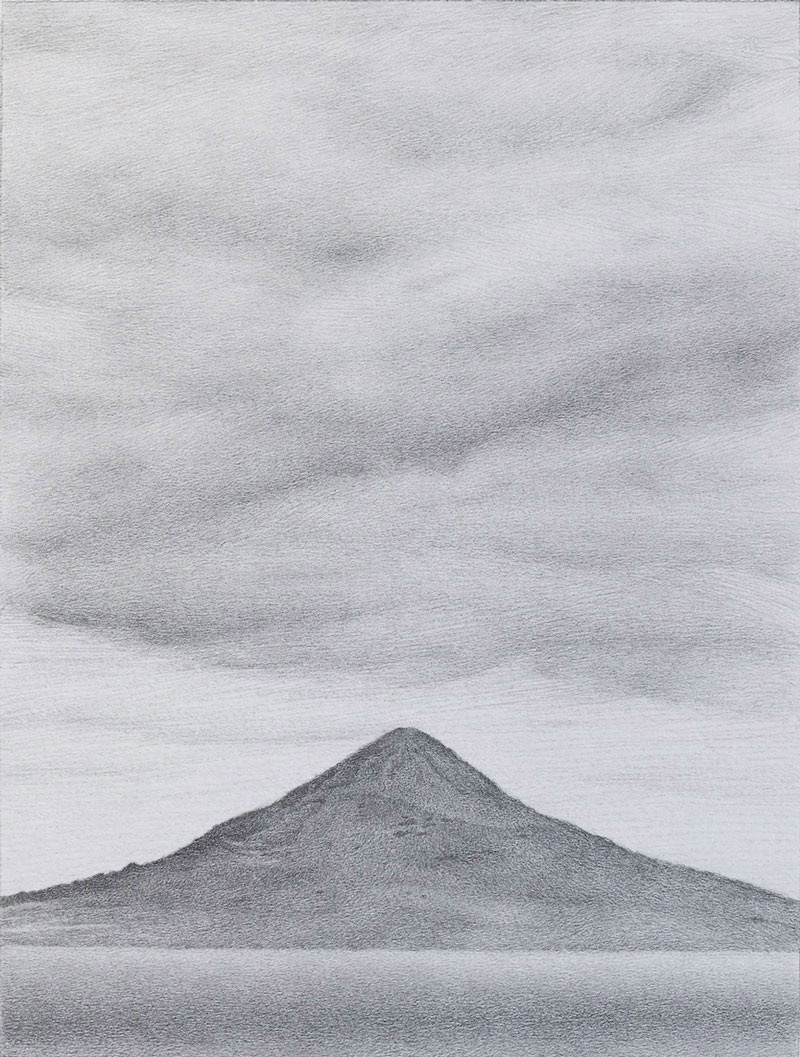

Michael Scott lives in an area south of Santa Fe free of light pollution, where he can step out of his home or his studio and see the expanse of the Milky Way spread across the sky. One of his painter heroes is the 19th century German romantic painter Caspar David Friedrich, who wrote,

“The artist should not only paint what he sees before him, but also what he sees within him.”

Michael Scott lives in an area south of Santa Fe free of light pollution, where he can step out of his home or his studio and see the expanse of the Milky Way spread across the sky. One of his painter heroes is the 19th century German romantic painter Caspar David Friedrich, who wrote,

“The artist should not only paint what he sees before him, but also what he sees within him.”

Michael’s next exhibition at Evoke is titled Habitat and the Preternatural, that miraculous state that is inexplicable by ordinary means. In his painting Moon Over Fire Hole, the fluid river falls over the solid rock of Yellowstone, but the two become one in the blue light. The moon appears almost incidentally with its reflected warm light.

I first experienced the phenomenon of blue “moonlight” at Prajna Mountain Forest Refuge north of Santa Fe on a Zen retreat with Roshi Joan Halifax. In the middle of the night I heard a noise and unzipped the flap of my tent to be greeted not by a hungry bear but by a world of luminous blue. Even when confronted with the miraculous, I am cursed to discover “Why?”.

The rods and cones in the eye turn light into electrical signals that the brain interprets as sight. The 19th century Bohemian physiologist Jan Evangelista Purkyně discovered that the light sensitivity of the eyes shifts to the blue end of the spectrum in low light conditions. My brain interpreted the message being sent to it as “blue light”.

In the gallery’s current exhibition, Lettera Amorosa, Esha Chiocchio has created a fan fold book of cyanotypes, a camera-less process of exposing light-sensitive paper to UV light and washing with water. The result is Prussian Blue images. There is a “why” or “how”. Paper or fabric is coated with a mixture of ferric ammonium citrate and potassium ferricyanide. The oxidation of potassium ferricyanide produces Prussian Blue.

In the gallery’s current exhibition, Lettera Amorosa, Esha Chiocchio has created a fan fold book of cyanotypes, a camera-less process of exposing light-sensitive paper to UV light and washing with water. The result is Prussian Blue images. There is a “why” or “how”. Paper or fabric is coated with a mixture of ferric ammonium citrate and potassium ferricyanide. The oxidation of potassium ferricyanide produces Prussian Blue.

The images in each of her two books are The Nature Collection and The Farm Collection reflecting her “deep love for the natural world and for the pastoral life most humans experienced before industrialization.” She has been photographing farms and regenerative architecture and enlarged the negatives to make her contact-printed cyanotypes.

On a recent artist residency in Chile, Esha did a lot of night photography and pondered how she could print cyanotypes on thin enough paper to be backed with silver, so the stars would be luminous. She is continuing to explore the possibilities and, meanwhile, printed these images on earthy, rough-edged Kozo mulberry paper from Japan.

When “Looking and Seeing”, there are many “aha” moments. Looking at Esha’s cyanotype Longing for the Sea, East Sooke, BC, Canada, I thought immediately of Caspar David Friedrich’s painting Wanderer above the sea of fog, ca. 1817.

I’ll just leave that moment here.

Esha Chiocchio, Longing for the Sea, East Sooke, BC, Canada, cyanotype, 6" x 6".

Above right: Caspar David Friedrich, Wanderer above the sea of fog, c.1817, Hamburger Kunsthalle, Hamburg, Germany.

Esha Chiocchio, Longing for the Sea, East Sooke, BC, Canada, cyanotype, 6" x 6".

Above right: Caspar David Friedrich, Wanderer above the sea of fog, c.1817, Hamburger Kunsthalle, Hamburg, Germany.

March 23, 2025

Soey Milk | Moon Baby Blue, Remember When You Fall Asleep, and White in Shade

When we began this series, we tried to have “one long look at one work of art.” I’ve veered off the path fairly often, taking the path less traveled by. I used to think an artist’s portfolio should be consistent. Perhaps it was Emerson who broke me of that. In his essay “Self-Reliance” he wrote, “A foolish consistency is the hobgoblin of little minds, adored by little statesmen and philosophers and divines. With consistency, a great soul has simply nothing to do.”

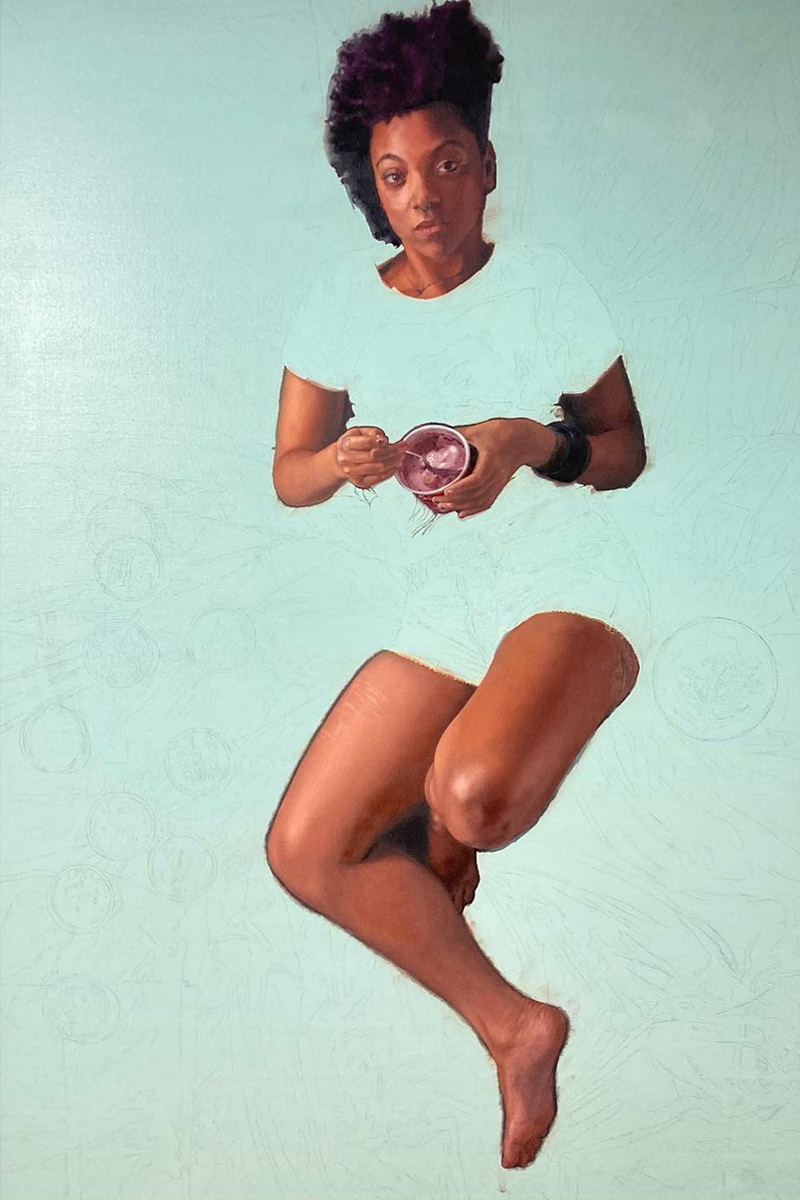

Today, I’m looking at three works by Soey Milk –two oil paintings and a graphite drawing. At first glance they appear to be by different artists, but they have a subtle, grounded consistency that embodies her connection to the world around her, her exploration of the media she uses and her relationship to the people in her life—the activities of a great soul. About her drawings, she writes, “I strive to capture the essence of the subject in front of me, translating its flesh and energy onto paper.”

At first glance, Moon Baby Blue, has to be by another artist than the one known for her sensuous figures in complex, painterly settings. Her meticulously-rendered cat with its luminous blue bow gazes out from a star-filled sky that seems, at first, to be a solid color but reveals many colors and texture on closer examination and begins to suggest that the artist is the same.

At first glance, Moon Baby Blue, has to be by another artist than the one known for her sensuous figures in complex, painterly settings. Her meticulously-rendered cat with its luminous blue bow gazes out from a star-filled sky that seems, at first, to be a solid color but reveals many colors and texture on closer examination and begins to suggest that the artist is the same.

Soey comments, “The Moon Baby Blue (and Moon Baby Pink) indeed marks a departure from my usual figurative work. This piece combines intricate realism with a lighter, more whimsical touch. Each strand and fuzz of the cat’s fur is carefully rendered to create a lifelike texture, while its glowing eyes add a captivating element. The backdrop, a serene yet playful night sky, gives the piece a soft charm. The balance between the highly detailed subject and the more stylized atmosphere brings a unique harmony that feels both engaging and soothing. It offers a fresh perspective, blending technical precision with an unexpected sense of warmth and wonder.”

Soey comments, “The Moon Baby Blue (and Moon Baby Pink) indeed marks a departure from my usual figurative work. This piece combines intricate realism with a lighter, more whimsical touch. Each strand and fuzz of the cat’s fur is carefully rendered to create a lifelike texture, while its glowing eyes add a captivating element. The backdrop, a serene yet playful night sky, gives the piece a soft charm. The balance between the highly detailed subject and the more stylized atmosphere brings a unique harmony that feels both engaging and soothing. It offers a fresh perspective, blending technical precision with an unexpected sense of warmth and wonder.”

Remember When You Fall Asleep No. 3 is immediately recognizable as a Soey Milk painting with the lips resembling the glaze on a fruit tart and the surrounding, flatly-painted, simplified flower blossoms.

Remember When You Fall Asleep No. 3 is immediately recognizable as a Soey Milk painting with the lips resembling the glaze on a fruit tart and the surrounding, flatly-painted, simplified flower blossoms.

She explains, “As for the 6" x 6" piece of ruby-red lips, it’s a study in both precision and symbolism. The lips are rendered in much detail, capturing the glossy, wet texture with subtle pink, red, and petal tones that give it a sensual depth. Surrounding the lips is a mandala-like pattern of flower petals, a recurring motif in my work. These petals aren’t simply decorative; they represent a deeper meaning. The center signifies the self, while the petals extending outward symbolize energy and connection.”

Soey’s drawings are “at the heart of my artistic practice,” she says, “acting as both a blueprint and an emotional exploration of the human experience. I strive to capture the essence of the subject in front of me, translating its flesh and energy onto paper. The act of drawing is deeply personal—each line is not just about precision, but about a connection that evolves through my own human lens. It’s a process that often involves steps back, but always moves forward, steadily refining the work to reveal the soul of the image.”

Soey’s drawings are “at the heart of my artistic practice,” she says, “acting as both a blueprint and an emotional exploration of the human experience. I strive to capture the essence of the subject in front of me, translating its flesh and energy onto paper. The act of drawing is deeply personal—each line is not just about precision, but about a connection that evolves through my own human lens. It’s a process that often involves steps back, but always moves forward, steadily refining the work to reveal the soul of the image.”

Her drawings recall the drawings of Ingres—wonderfully controlled mark making and areas that appear to have appeared by magic.

In White in Shade, a black cord is draped across the figure, a motif that often appears in her paintings. She explains, “The props I incorporate, particularly the silk ropes and cords, go beyond simple compositional tools. They carry a deeper meaning, symbolizing life and relationships. Just as ropes intertwine, stretch, or knot, so do the connections between people. They fuse, unravel, or shift, but always leave their mark. These ropes reflect the strands of life and the ways in which we come together, change, or evolve. As I navigate my own journey, my work becomes a visual timeline—a way to reflect on the relationships and experiences that shape me.

In White in Shade, a black cord is draped across the figure, a motif that often appears in her paintings. She explains, “The props I incorporate, particularly the silk ropes and cords, go beyond simple compositional tools. They carry a deeper meaning, symbolizing life and relationships. Just as ropes intertwine, stretch, or knot, so do the connections between people. They fuse, unravel, or shift, but always leave their mark. These ropes reflect the strands of life and the ways in which we come together, change, or evolve. As I navigate my own journey, my work becomes a visual timeline—a way to reflect on the relationships and experiences that shape me.

“For those who engage with my art, these recurring motifs—ropes and connections—offer a window into a deeper narrative. Each piece not only represents the figure before me, but also tells a story of relationships, growth, and the marks we leave on one another" . . .

March 9, 2025

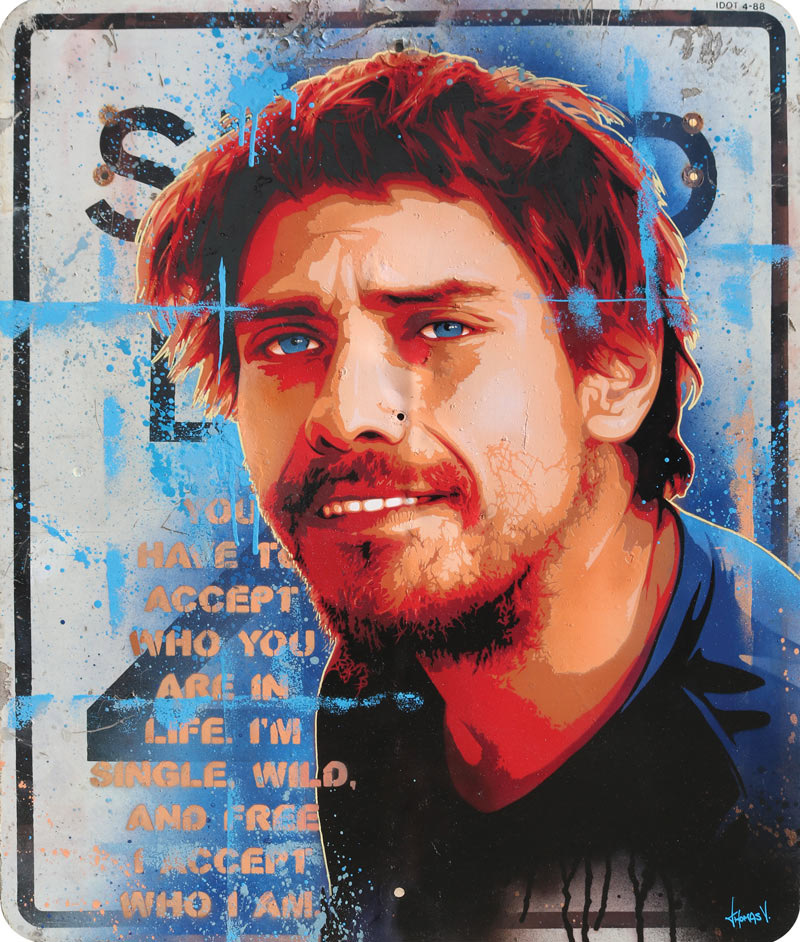

Kent Williams | Self-Portrait as Rodin's Striding Man, with Appendages

A contemporary artist, Kent Williams reveres art and artists of the past and sometimes incorporates their work into his paintings. In his 84 by 144-inch diptych, Self-Portrait as Rodin's Striding Man, with Appendages (Redux) 2000, 2018, he becomes a sculpture of Auguste Rodin (1840-1917).

“I’m a huge fan of Rodin,” he says. “He’s in my top 5. I can’t imagine anyone having more love and respect for his work than I have. I understand it so completely, I feel I could be a sculptor. I never pursued it, however, because of time and being committed to the next show or whatever. I’m the person who wants to do it full on, not just pick at it. I want to see what I can do, fully.”

He relates that when Rodin exhibited his plaster model of “The Age of Bronze” at the 1877 Paris Salon, he was accused of casting the figure from a “commonplace” live model. The naturalistic pose and modeling went against the grain of those preferring the idealistic poses and musculature of classical sculpture.

The following year, Rodin began modeling “Saint John the Baptist Preaching”, larger than life-size to prove his ability.

Rodin was inspired by and collected fragments of classical sculpture and said, “these divine fragments . . . move me more profoundly than living persons.”

Rodin used fragments of his own sculpture to create “L’Homme qui marche”, the sculpture Kent used in his “Self-Portrait . . .” The Musée Rodin in Paris relates, “This work with a complex genesis illustrates how receptive Rodin was to the English sculptor Henry Moore’s belief that an artist should ‘reconsider and rethink’ an idea…. [T]he sculpture was conceived in 1899-1900, using studies for the torso and legs of Saint John the Baptist, dating from 1878 . . . The resultant figure is marginally out of true; the torso leans forward and swivels slightly to the left. The impression of movement is heightened by the barely perceptible inaccuracy of the adjustments.”

Kent remarks, “Life is fragmented. It’s not as simple as I first imagined. It’s a battle to stay organized. When I was finished with a show, I used to clean up my studio and start fresh. I used to have the time. Maybe as you get older, time does go faster.

“Most of my art deals with the human condition and is sometimes wrapped around myself and where I am. That touches on things a lot of people experience and feel. Being able to relate to someone else going through similar things can bring comfort to people –knowing you’re not alone.

“In 1999, I chose Rodin’s sculpture “L’Homme qui marche” (The Striding Man), to use as a vehicle for what I was going through—a deep dark place.” He made several paintings on the theme, with himself as a striding man. “The sculpture is fragments, and I had to represent my own fragmentation at the time.”

“I was going through that dark period from a variety of things. My biological son and my adopted son were young and about the same age and, in my dark place, it was hard to deal with their being cholicy, crying, teething. But I discovered how that stage leaves fast, and another stage arrives and passes. When you realize they pass, they’re easier to deal with.”

The painting depicts him striding forward (“I’m going to walk out of this dark period.”). In a disjointed way, he holds the hands of his sons. “My boys are important to me,” he says. “It was my burden, not theirs. I never wanted them to feel unsafe. They didn’t know what I was going through or what I was showing in the painting. When they came into the studio to model, I gave them brushes to paint a little along the bottom of the painting.”

When he turned to the painting years later, he felt it was unfinished. “My ideas had developed without losing the thrust of the piece,” he says. “I thought that I would take away and obscure things. The big white shapes were a new abstract element, my first pass at obscuring. I would take it farther as time passed.”

Today, drawing is an important part of his process. “I’ll start painting,” he says, “and, if I’m successful, I’ll maintain the drawing aspect while allowing myself to be bold with the brushwork. I want to maintain some of that linear suggestion and straightforwardness. The act of painting, though, wants to push away from the simple line drawing. I work in many layers. Each pass is very broad, and the painting starts to refine itself in certain areas. If I begin to lose what I like, I sand it back down to a certain degree and knock enough paint off to allow the line to show through.”

The poet and writer of fiction, Dorothy Parker (1893-1967), known for the best acerbic wisecracks, was also observant and had more profound insights, writing, “Art is a form of catharsis, emotional release, purging, cleansing, purifying.”

February 23, 2025

Jeremy Mann | A Place I Stopped on the Way to Town #1

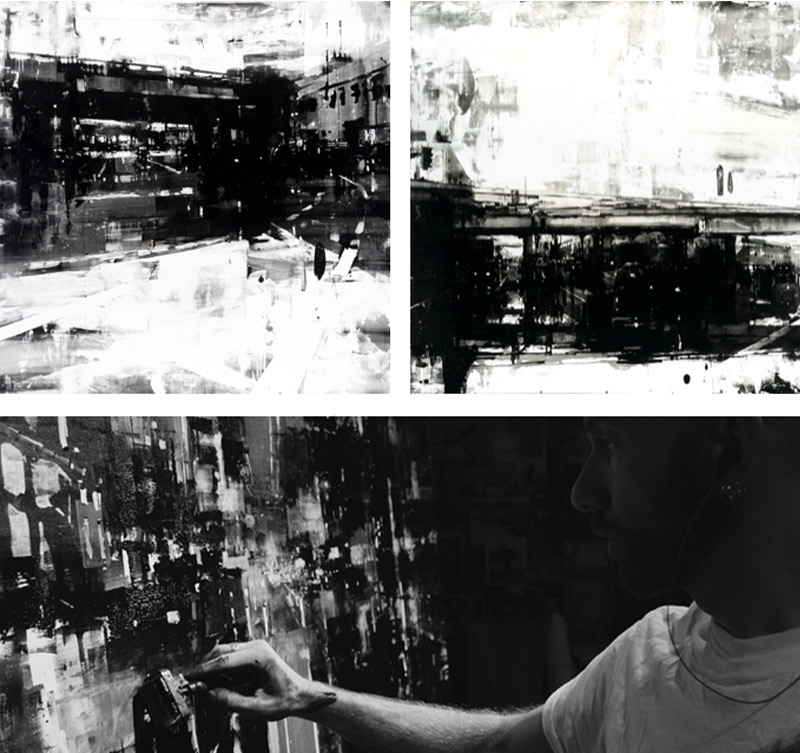

New among the works of Jeremy Mann are small 5" x 4” oil on papered panel paintings of a forest. They are a striking departure from the brooding San Francisco cityscapes I had first seen over 20 years ago. Both of our lives have changed since then. I now live in a converted adobe goat shed in the high desert of New Mexico and Jeremy now lives with his wife, the artist Nadezda, in an 18th century farmhouse “in the middle of a national park of forested mountains” in Spain.

I had admired his dark, brooding, paintings of the city about which he told me, “I think the grey and the sad is beautiful, and nothing moves my heart more than to be able to paint it.” I wasn’t prepared for his forest paintings, especially A Place I Stopped on the Way to Town #1 with its dark depths, glowing green lichen and the color he found in everything.

I had admired his dark, brooding, paintings of the city about which he told me, “I think the grey and the sad is beautiful, and nothing moves my heart more than to be able to paint it.” I wasn’t prepared for his forest paintings, especially A Place I Stopped on the Way to Town #1 with its dark depths, glowing green lichen and the color he found in everything.

On his Instagram page, he wrote, “I always wanted to paint the inside of a forest, and I thought it was going to be difficult, so I didn’t. Now, living in a forest, I’m addicted. And I was right.”

On his Instagram page, he wrote, “I always wanted to paint the inside of a forest, and I thought it was going to be difficult, so I didn’t. Now, living in a forest, I’m addicted. And I was right.”

As a lover of trees and forests, sitting or walking quietly and absorbing the richness of color and texture above ground and contemplating the unfathomable complexity of the flora communicating below its surface, I wanted to know how, after the chaos of the city, Jeremy was responding to his new environment. As expected, he didn’t let me down.

Today he walks through the forest on the way to the bakery in town 4 km away. This little painting is one of a series he is working on. “I was always looking at the world as things I would have to render,” he says, “and that would make any dense forest daunting to anyone. To progress myself, I learned long ago to do more than one of the same thing, and often the second one is more free, more inventive, more me.

Today he walks through the forest on the way to the bakery in town 4 km away. This little painting is one of a series he is working on. “I was always looking at the world as things I would have to render,” he says, “and that would make any dense forest daunting to anyone. To progress myself, I learned long ago to do more than one of the same thing, and often the second one is more free, more inventive, more me.

Financial problems precluded his finishing his studio, “pleasantly forcing me to indulge in my dream of painting plein air as often as possible, my little paint box and the endless natural beauty around me became my new studio where this practice of multiple paintings in one sitting grew to show me what I knew, but didn’t understand; the natural world is just a reference to guide us, not to be duplicated. To be inspired by, not to try and replicate, a reference. A thing to ‘refer’ to, not to mimic. Forcing me to decide what I want to do on the panel in front of me out there in the still and beautiful forest, forcing me to focus on the language of brushwork and color. Forcing me, to accept and see change as new challenges to garner experience from. I changed my palette completely to only the simple but saturated tertiaries because I wanted to understand color and light at a different level, knowing this can only be gleaned from life and making those two elements the most important thing for me to stay focused on while sitting there in the forest or at the edge of the moving Mediterranean seaside.”

Financial problems precluded his finishing his studio, “pleasantly forcing me to indulge in my dream of painting plein air as often as possible, my little paint box and the endless natural beauty around me became my new studio where this practice of multiple paintings in one sitting grew to show me what I knew, but didn’t understand; the natural world is just a reference to guide us, not to be duplicated. To be inspired by, not to try and replicate, a reference. A thing to ‘refer’ to, not to mimic. Forcing me to decide what I want to do on the panel in front of me out there in the still and beautiful forest, forcing me to focus on the language of brushwork and color. Forcing me, to accept and see change as new challenges to garner experience from. I changed my palette completely to only the simple but saturated tertiaries because I wanted to understand color and light at a different level, knowing this can only be gleaned from life and making those two elements the most important thing for me to stay focused on while sitting there in the forest or at the edge of the moving Mediterranean seaside.”

He recalls an incident in California where he learned to be still. “When I was painting in the west with many artists, we all set up our easels and dove into chasing that final product, the finished painting. It wasn’t but almost 30 minutes into my endeavor that I turned and saw an older, wiser man still staring out across the seemingly still landscape with not a single mark upon his canvas. Absorb, lest we simply wring a dry rag hoping for a sale. Much of the art life I began my career in was based upon that daily wringing. There is much, so so much more to creating than knowing your brushes, surfaces, mediums, forms, color harmonies and compositions, all the foundations we are taught and seek throughout our careers are missing some very important tools to master, so seemingly useless to the artist seeking a profit from a product, but indispensable when seeking a life of happiness creating unbounded and in peace. Knowing what to choose to paint, why we choose it, what we truly wish to say and how to say it, and how to put things in our hands to bring that vision to life has nothing much to do with material matters.

“This is where I began to see the richness of life, when I learned to sit still, in body and mind, that it was OK to sit still, that thinking and seeing are just as important tools as brush and surface, and come to know the nature I was roaming. That appreciation gave me some deeper knowledge which was missing in my practice. Sit, and look. Look long enough, sit still long enough, clear the mind of the rabble which has nothing to do with the moment of painting, and life provides us with a fantasy of forms, colors, harmonies, compositions, creatures, sounds and feelings we don’t get to experience running through the rat race of modernity’s distracting traps.”

Escaping the vagaries of the art world and life in the city has been difficult but, he is beginning to enjoy the freedom of sitting in the forest with his thermos of tea, looking and seeing. “Letting color and composition find a balance based on my desire to emote the feeling of being with me in that shady spot, and not worrying about having to make anything at all, to just be, to be in a state of creativity, spending time aware, absorbing and playing with colors and marks like any good forest child would do without responsibilities. I was beginning to truly see the reality of painting, that it’s about making an image in whatever way we like and not duplicating a rendering of an already existing reference. All of this is making great headway in the concurrent studio pieces in the works.”

Escaping the vagaries of the art world and life in the city has been difficult but, he is beginning to enjoy the freedom of sitting in the forest with his thermos of tea, looking and seeing. “Letting color and composition find a balance based on my desire to emote the feeling of being with me in that shady spot, and not worrying about having to make anything at all, to just be, to be in a state of creativity, spending time aware, absorbing and playing with colors and marks like any good forest child would do without responsibilities. I was beginning to truly see the reality of painting, that it’s about making an image in whatever way we like and not duplicating a rendering of an already existing reference. All of this is making great headway in the concurrent studio pieces in the works.”

Recently, Jeremy posted one of his forest paintings with a cryptic description of his day. “Took a hike up in the mountain, painted some trees, chased some sheep.”

February 8, 2025

Lynn Boggess | 16 June 2023

Lynn Boggess and Andrew Wyeth grew up in East Coast farmland, Lynn in West Virginia and Wyeth in Pennsylvania and Maine. “When I saw his work,” Lynn says, “I related to it directly.”

He was introduced to Wyeth’s watercolors by an enthusiastic junior high school art teacher. “His quick study watercolors were a huge influence,” Lynn explains.

“I like abstract expressionism,” he continues, “which is why I related to his watercolors. His egg tempera paintings show masterful control but I find them way too tight.”

Only a few of Wyeth’s abstract watercolors were available to the public during his lifetime, but in 20023/24, the Brandywine Museum of Art showed over 70 works from Andrew and Betsy Wyeth’s private collection in the exhibition Abstract Flash: Unseen Andrew Wyeth.

Wyeth had written, “My struggle is to preserve that abstract flash – like something you caught out of the corner of your eye, but in the picture you can look at it directly.”

Elsewhere he wrote, “With watercolor, you can pick up the atmosphere, the temperature, the sound of snow shifting through the trees or over the ice of a small pond or against a windowpane. Watercolor perfectly expresses the free side of my nature . . . The brain must not interfere. You’re painting so constantly that your brain disappears, and your subconscious goes into your fingers and it just flows.”

His comments might have been made by Lynn who, although he paints with oil, has a keen sense of composition and often enters a meditative state as he gazes at the landscape and creates his paintings.

He has said, “Landscape paintings are philosophies encased in compositions. This really is a very complex, critical question. I avoid using the Golden Section and prefer focal points either in the middle or on the edges because they allow the space to be read simultaneously as a flat abstraction and as a recessional depth–something that helps me understand the paradoxes of life in general. That paradoxical experience is also emphasized in the illusion of space and the thick texture of the paint.”

He has said, “Landscape paintings are philosophies encased in compositions. This really is a very complex, critical question. I avoid using the Golden Section and prefer focal points either in the middle or on the edges because they allow the space to be read simultaneously as a flat abstraction and as a recessional depth–something that helps me understand the paradoxes of life in general. That paradoxical experience is also emphasized in the illusion of space and the thick texture of the paint.”

If the unlikely passerby could see Lynn painting at his unlikely sites, they would see him paint with a trowel on large canvases mounted on a portable studio he has carted into the wild, standing on its wood floor under its canopy. His wife, Jennifer, has written about his choice of sites. “Being on site gave him a certain empathy with the land. Subjects that he found most fascinating were those in which there was evidence of a struggle. He was drawn to broken trees, wind-swept rubble, great boulders, and flood water. That connection remains in his mature work, which is heroic in its subject and process. As the paintings have become larger, the discipline of being present continues. An assembly of easels, boxes, and scaffolds is necessary to bring the canvas to the subject. The work is created in all kinds of weather and on all types of terrain.”

This week’s Looking and Seeing painting is his 16 June 2023, capturing a moment in time. I chose it from the many other paintings that attracted me because it had water, rocks and vegetation. His other paintings have water, rocks and vegetation but this had a certain, what I hesitate to call a certain je ne sais quoi depicting a not particularly “photogenic” scene.

This week’s Looking and Seeing painting is his 16 June 2023, capturing a moment in time. I chose it from the many other paintings that attracted me because it had water, rocks and vegetation. His other paintings have water, rocks and vegetation but this had a certain, what I hesitate to call a certain je ne sais quoi depicting a not particularly “photogenic” scene.

Lynn, of course, knew what the “quoi” was that attracted him. “I want to see a scene that has something to say,” he explains--rock and water, contrast. The trees create an infinite space. I’Il get into the trees and set up my little meditative shelter. I meditate on what is transpiring in front of me, the movement in the water, the solid rocks and trees. You need both.”

Water and rock are adversaries even deep in the West Virginia woods. We’re familiar with the ocean crashing against the rocky shore, but their adversarial relationship also takes place in quieter ways. Water seeps into cracks in the rocks and, when it freezes, breaks the rocks apart, continuing their gradual erosion which creates soil in the which the trees and plants can grow.

Echoing Wyeth’s abstract flash caught out of the corner of his eye that he could paint so the viewer would see it directly, Lynn often avoids the centrality of the Golden Section, as he says, and allows the eye to travel around the composition.

Echoing Wyeth’s abstract flash caught out of the corner of his eye that he could paint so the viewer would see it directly, Lynn often avoids the centrality of the Golden Section, as he says, and allows the eye to travel around the composition.

His thick impasto of oil paint is applied with a trowel. Although I marvel at the awesome detail and subtle luminosity of nearly photographic realism, I love paint—it’s lush viscosity, it’s having its own mind.

“I was still into the discipline of painting at the time and discovered the playfulness and chaos of moving the paint around. When I accessed this textural thing, it was the freedom I was looking for. Painting wet on wet is half accident, and I learned by trial and error. It’s a hard way to learn but you never forget it. You don’t know exactly what’s going to happen but you kind of know within a bracket.

“What I try to get are areas of quiet, and areas of increased activity building up to a crescendo—not just one emotion. I start off in high gear and at the very end of the experience I slow and resolve awkward areas, sometimes back in the studio.

The thick paint and trowel gestures give the paintings a multidimensional quality. “The thickness of paint functions as much as hue,” he says, “Lit correctly, the paint functions as a relief sculpture.”

I was attracted by the water in 16 June 2023, its movement and reflections as well as the dimensionality and dimensionless qualities of its ripples. Rising up from the water are planar rocks and a cacophony of trees, branches, leaves and gradations of light.

I was attracted by the water in 16 June 2023, its movement and reflections as well as the dimensionality and dimensionless qualities of its ripples. Rising up from the water are planar rocks and a cacophony of trees, branches, leaves and gradations of light.

He explains, “I’m trying to document an experience. I’m not just doing images. I could do that sitting at home with an iPad. I do realism, not naturalism. Realism adds an emotional element. All those forms are in flux and I don’t paint exactly what I’m looking at. If I sat in the studio I would become idealistic. I have to have the tactile grittiness of nature. I try to understand it and give it something of myself and what I think.

“You can’t just go out and expect nature to speak to you. It’s not going to happen. You have to engage with nature, meet it in the middle.”

January 26, 2025

Michael Scott | Religion Meets Science

Mushrooms emerging from the forest floor providing nourishment for our bodies and our psyches—and, sometimes, bringing death—are the fruiting structures of fungi whose vast root systems called mycelia can inhabit nearly 4 square miles of turf as the fungus Armillaria ostoyae does in Oregon’s Blue Mountains. Not only is it large, it is estimated to be over 2,400 years old.

Trees, through photosynthesis, produce sugars and fats that the fungi absorb into their mycelium which, in turn, help the trees and other plants absorb water and nutrients from the soil far away from their root systems. They also form a huge network of communication among the forest flora.

The unseen physical connections in the natural world parallel its non-physical connections. The 13th-century priest and theologian, Thomas Aquinas, wrote about the preternatural. For his 2022 exhibition, Preternatural, at the Cincinnati Museum Center, Michael Scott wrote, “Somewhere between the mundane and the miraculous, exists the preternatural. That is what I have tried to paint with my sojourns to these wild places in America that offer us a glimpse of why we need to protect certain lands.

“Aquinas coined the word,” he observes. “The more I looked into it, I could explain it this way; The natural is what we exist in normally every day. You look out, and there’s the natural world. Then, there’s the supernatural, which is like an idea that’s very hard to prove, but it does exist. Aquinas was more interested in what happens in the moments in your life when you’re looking at something which is natural, but experience something beyond. If you go into the natural world and camp out, you may not get it the first day. You may not get it the second day, but if you’re experiencing the land, it will come and it will be there for you. It never fails—that moment of transcendence when it is no longer a literal experience.”

He explains, “The landscape has always offered me an invitation to enter the realm of the preternatural—a world of stillness, reflection, and phenomena far removed from the mundane activities of daily life. While I engage in this conversation with nature, logic and reason are often suspended. Indeed, the cold facts of the physical world could not be more dissimilar to the pure sensations derived from our wild places. These elements are what I instinctively and explicitly seek as a painter, not to restrict the landscape to a simple imitation but to participate in a conversation with the unknown.

“When I was up in Canada painting a landscape, the full moon was rising in front of me as the sun was setting behind me. It really shook me up. It was one of the coolest moments I’ve experienced in a long time.”

The preternatural sometimes manifests in synchronicities that shake the soul and remove the barriers between us and the other. Painting an image of a stag for his upcoming summer exhibition at Evoke he walked over to look out the glass doors opening onto the vast landscape surround his home and studio, “And there was a stag! We looked at each other and then he walked down and sat under a juniper and was just as peaceful as anything.” The gaze of the stag in his painting is now more communicative than it might have been before their meeting and the slight tilt of his head suggests a sympatico, a shared relationship of being.

The preternatural sometimes manifests in synchronicities that shake the soul and remove the barriers between us and the other. Painting an image of a stag for his upcoming summer exhibition at Evoke he walked over to look out the glass doors opening onto the vast landscape surround his home and studio, “And there was a stag! We looked at each other and then he walked down and sat under a juniper and was just as peaceful as anything.” The gaze of the stag in his painting is now more communicative than it might have been before their meeting and the slight tilt of his head suggests a sympatico, a shared relationship of being.

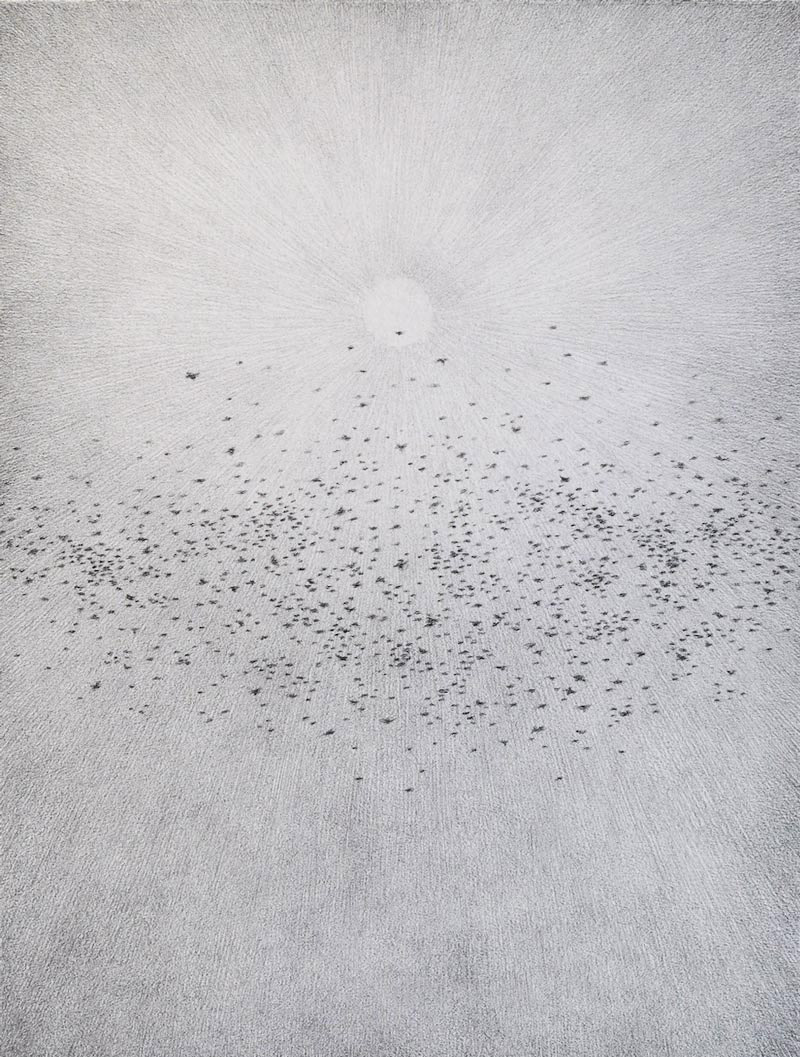

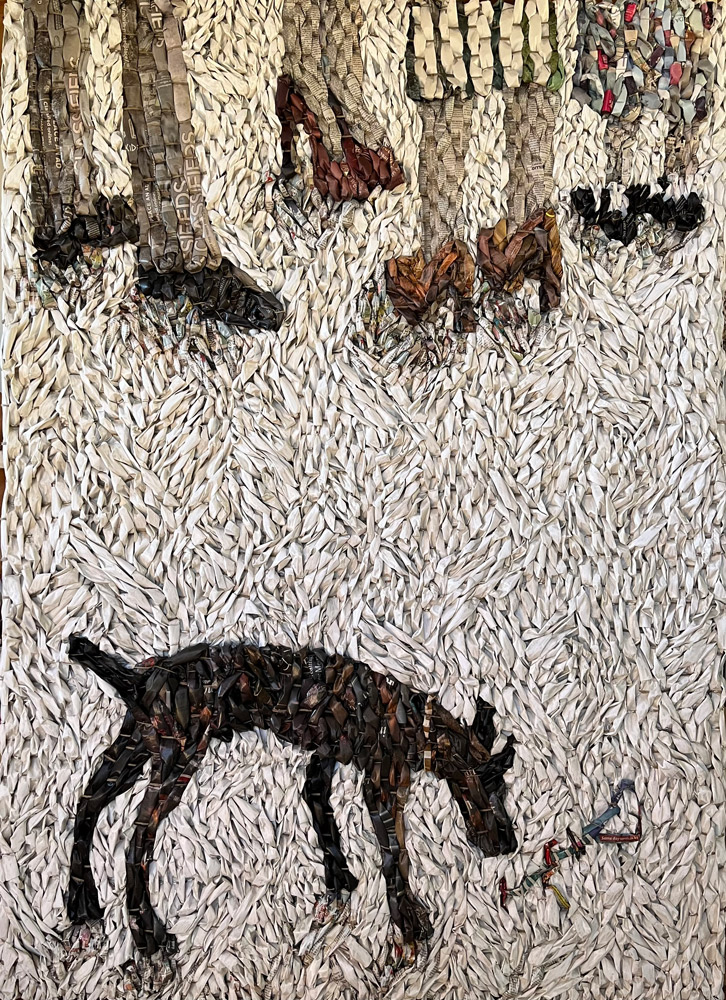

Beneath the forest floor are the mycelia, perfectly performing their role. Beneath the surface of Michael’s painting Religion Meets Science, lies an image that didn’t perform its role. As is his wont, he meticulously rendered a trumpeter swan, once nearly extinct in the Yellowstone region.

Beneath the forest floor are the mycelia, perfectly performing their role. Beneath the surface of Michael’s painting Religion Meets Science, lies an image that didn’t perform its role. As is his wont, he meticulously rendered a trumpeter swan, once nearly extinct in the Yellowstone region.

“It’s a beautiful bird,” he comments. “It’s very majestic in its own right, but it’s been used in narratives for centuries. It was too much of a naturalist painting. Although I rendered it to the hilt, it really didn’t say anything.”

The pure white swan is burned in Religion Meets Science, its blackened wings spread out as if on a cross but more closely recalling the wings on the caduceus, the symbol of medicine with its staff entwined with snakes derived from the staff of the Greek god Hermes.

The elements of earth, air, fire and water are ever present themes in Michael’s paintings.

The elements of earth, air, fire and water are ever present themes in Michael’s paintings.

“As I was creating this body of work,” he says,” it migrated to the elements. Today, we’re dealing with floods, we're dealing with tornadoes and hurricanes, we're dealing with erupting volcanoes, wildfires and landslides. So, all four of the elements are integral in what I'm painting. I have been painting fire paintings for quite a long time, partly because I find fire to be so mysterious. It is not only something that destroys, but it is also something that renews.”

For thousands of years, Native people have practiced cultural burning, a spiritual and practical method of land management. The burns encourage biodiversity, new growth and a more resilient landscape.

Perhaps my most favorite of Michael’s fire paintings, although there are many, is The Witness. Several years ago I wrote:

Perhaps my most favorite of Michael’s fire paintings, although there are many, is The Witness. Several years ago I wrote:

“In The Witness, the four elements interweave, smoke and mist combining in a liminal state like the place between waking and sleeping, visible and not visible, real and unreal, present and past. A fire burns from among ferns and lichen-covered rocks. The wolf becomes revealed and sees what else is revealed. Michael notes that the wolf ‘characterizes a symbol of guardianship and ritual.’ Among Native peoples the wolf is often a spiritual guide.

“In this painting the wolf appears to observe Earth in a primeval state before mankind or, perhaps, after. Despite our efforts to right our wrongs, cutting down on carbon emissions, reintroducing bison and wolves to their historical habitats we, as a species, may not survive. Michael offers hope as well as warnings in his paintings and that the non-material may be our destiny.

“’The “gray zone” of the smoke and fog crosses all belief systems and is a state between reality and unreality,’ he says. ‘It is both real and imagined at the same time as it confronts the viewer in both physical form and sprit. The smoke symbolizes the transition of matter into sprit and sends signals that represent the material manifestation of the soul’s journey.’”

The observing wolf reminds me of a story Northwest Native elders told the children when they asked what they should do if they got lost. David Wagoner interpreted it in his poem Lost:

Stand still. The trees ahead and bushes beside you

Are not lost. Wherever you are is called Here,

And you must treat it as a powerful stranger,

Must ask permission to know it and be known.

The forest breathes. Listen. It answers,

I have made this place around you.

If you leave it, you may come back again, saying Here.

No two trees are the same to Raven.

No two branches are the same to Wren.

If what a tree or a bush does is lost on you,

You are surely lost. Stand still. The forest knows

Where you are. You must let it find you.

January 12, 2025

ESHA CHIOCCHIO | First Tracks II

Esha Chiocchio says, “I think of soil as a very precious thing and am interested in soil and land restoration, healing the damage people have done on this planet.”

Her photographs document the traditional annual remudding of the Great Mosque of Djenné, Mali, West Africa, for “National Geographic Magazine” and the rebuilding of miles of grasslands in the Lordsburg Playa in southwestern New Mexico for which she was awarded a 2023 National Geographic Explorer storyteller grant.

The mud buildings of Djenné suit their environment with thick walls that make cool interior spaces. The torrential downpours of the rainy season ravage the mud, however, and it needs to be replenished each year. Esha describes the work as “a slippery, messy scene with mud flying in all directions, people yelling instructions, kids laughing, people chanting – community chaos at its best.” Esha was a Peace Corps volunteer in Mali in 1997-1999.

She notes different conditions at Lordsburg. “In the late 1880s, when settlers founded Lordsburg in Southwestern New Mexico, a sea of grass tickled their horses' bellies and provided ample feed for their growing herds of livestock. By 2015, cattle had eaten the grass to the ground, and dust storms frequently enveloped Interstate 10, causing over 40 fatalities along a 20-mile stretch of highway since 1965.”

The entire community comes together to remud the Great Mosque and a handful of people are working with government agencies to restore the tickling grass of Lordsburg.

In both cases, in addition to the work itself, Esha is captivated by the people doing the work. Her photographs are “stories of hope, people doing things to shift our direction.”

We spoke at length about photography as fine art. At various points in my career I’ve beat the drum for photography as fine art and craft (pottery, glass, weaving, etc.) as fine art, including all of it in exhibitions of paintings drawings and sculpture. We couldn’t come up with a definition of “fine art” but agreed that Kathrine Erickson perhaps elevated documentary photography into that realm with the exhibition of Esha’s photographs, Restoring Earth’s Canvas, in 2023.

We spoke at length about photography as fine art. At various points in my career I’ve beat the drum for photography as fine art and craft (pottery, glass, weaving, etc.) as fine art, including all of it in exhibitions of paintings drawings and sculpture. We couldn’t come up with a definition of “fine art” but agreed that Kathrine Erickson perhaps elevated documentary photography into that realm with the exhibition of Esha’s photographs, Restoring Earth’s Canvas, in 2023.

Esha did come close to a definition, though, when she said, “Fine art for me is an image that has an engaging power to it such that a person wants to linger on that image.”

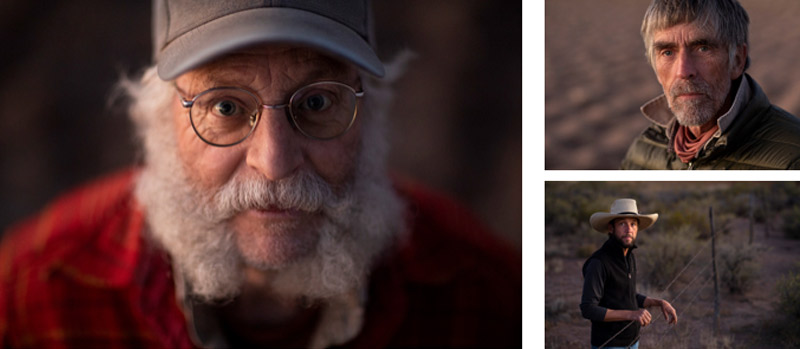

Among the photographs in the exhibition was First Tracks II, an aerial shot from her drone showing the erosion of the playa and a mysterious patterned ribbon along the top of the image. The photo is an intimate 6 x 9” pigment print with Moon Gold leaf on archival Mylar.

Moon Gold leaf is a blend of gold, silver and palladium with a softer color than gold leaf made with gold and copper. She explains that it “gives the land a luminance worthy of its profound importance to our collective future.”

The mysterious patterned ribbon is the mark making of Gordon Tooley, one of the three dedicated environmentalists working to restore the Playa. He is the proprietor of Tooley’s Trees and Keyline Design in Truchas, NM. His mark making takes place in three stages: first, he recontours the land with a keyline plow that oxygenates the soil, then uses a seeder and then an imprinter that makes pockmarks to capture rainfall.

The mysterious patterned ribbon is the mark making of Gordon Tooley, one of the three dedicated environmentalists working to restore the Playa. He is the proprietor of Tooley’s Trees and Keyline Design in Truchas, NM. His mark making takes place in three stages: first, he recontours the land with a keyline plow that oxygenates the soil, then uses a seeder and then an imprinter that makes pockmarks to capture rainfall.

When I asked her why, among a predominantly black and white exhibition, her portraits of the environmentalists were in color, she immediately replied that “these are colorful people and Gordon was wearing a deep red flannel shirt”.

When I asked her why, among a predominantly black and white exhibition, her portraits of the environmentalists were in color, she immediately replied that “these are colorful people and Gordon was wearing a deep red flannel shirt”.

Mike Gaglio owns High Desert Native Plants, in El Paso, TX, and selected gamma grasses, alkali sacaton, fourwing saltbush and len-scale saltbush for the project, all suited to the harsh terrain.

Van Clothier owns Stream Dynamics in Silver City, NM, and works to restore damaged watersheds. In her article on Esha and the Lordsburg project for “Evokation”, Kate Nelson quotes Van Clothier: “We work seamlessly together. We work, we camp, we have yummy food. We have beautiful sunrises and sunsets. We’ve watched rains and storms, seen the tremendous success of the project—and we’re having the time of our lives out there.”

Esha has a Master of Arts degree in Sustainable Communities from Goddard College. “I was interested in sustainable communities,” she explains, “investigating how do we regenerate the earth and make it beautiful and whole. But, photography kept calling me back to it after my husband and I raised our family. It feeds my soul on a certain level. I want to tell stories—stories of hope and of people doing things to shift our direction.”

Esha has a Master of Arts degree in Sustainable Communities from Goddard College. “I was interested in sustainable communities,” she explains, “investigating how do we regenerate the earth and make it beautiful and whole. But, photography kept calling me back to it after my husband and I raised our family. It feeds my soul on a certain level. I want to tell stories—stories of hope and of people doing things to shift our direction.”

Mike Gaglio summed up Esha’s talent in Kate Nelson’s essay: “This is a tough site to be on. It takes a special person to see the beauty. It takes work. Esha’s pictures are so deep. There’s such a soul to them.”

“Another photo in the exhibition was Morning Train, a color, archival pigment print, 40-inches wide of the Playa after a rain. Esha says “The train image needs to be large to be read properly. I got up early and went out to see what was going on. There was fog that morning and a train was passing in the distance. It was trains that opened up the land for ranchers and allowed them to get their cattle out to market. Heavy grazing consequently caused the grasslands to virtually disappear.”

“Another photo in the exhibition was Morning Train, a color, archival pigment print, 40-inches wide of the Playa after a rain. Esha says “The train image needs to be large to be read properly. I got up early and went out to see what was going on. There was fog that morning and a train was passing in the distance. It was trains that opened up the land for ranchers and allowed them to get their cattle out to market. Heavy grazing consequently caused the grasslands to virtually disappear.”

Explaining her documentary work of people around the world, she says, “When I’m photographing someone, I immerse myself in their world and ask questions. Basically, I want to shine love on them. I want them to feel seen and that their work is important. The world should be interested in what they do. I choose subjects that interest me and people who have stories that the world needs to hear. My hope is to photograph people in a way that love comes through.”

Explaining her documentary work of people around the world, she says, “When I’m photographing someone, I immerse myself in their world and ask questions. Basically, I want to shine love on them. I want them to feel seen and that their work is important. The world should be interested in what they do. I choose subjects that interest me and people who have stories that the world needs to hear. My hope is to photograph people in a way that love comes through.”

Andrew Wyeth, a fine artist whose work was often dismissed as illustration, said, “One's art goes as far and as deep as one's love goes."

December 29, 2024

HARRIET YALE RUSSELL | Sintra

Harriet Yale Russell (1939-2023) received her MFA in Painting in 1994 from the San Francisco Art Institute where Richard Diebenkorn (1922-1993) had been a student and an instructor. Diebenkorn was one of her artist influences throughout her career.

He once said, “Do search, but in order to find other than what is searched for.” Since I never met Russell I’ve learned about her through the writing of others who knew her and by looking more closely at her art. Doing some research on my own, however, I found “other than what is searched for” (otherwise known as going down a rabbit hole).

Russell was born in Rochester, NY. Her mother was a painter and her father was a chemist with Eastman Kodak Company. One of the interesting rabbit hole tidbits is an article in the December 27, 1957 “Democrat and Chronicle” in Rochester titled “Debutantes’ Night: 13 Introduced to Society at Annual Symphony Ball”. Among the young women was 18-year-old Harriet Yale Russell who “wore peau de soie with a flowing skirt fastened at the back with two pink roses”. Her Yale ancestry goes back to the early settlers of New Haven, CT. Yale College was founded in 1701 and named after an early benefactor, Elihu Yale.

She attended the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, where she received her degree “with distinction” in the Department of Graphic Arts. She taught etching at the school for 10 years and in 1969 received it’s Clarissa Bartlett Traveling Scholarship for a year of travel in Portugal.

Among her paintings at Evoke is Sintra, recalling the picturesque resort town of Sintra, near Lisbon.

In her essay in the January 2023 issue of “Evokation”, Mara Christian Harris recalls Post-it notes in Russell’s studio, one of which contained the phrase “Listen to the paint.” The phrase recalls Diebenkorn who wrote, “I don't go into the studio with the idea of 'saying' something. What I do is face the blank canvas and put a few arbitrary marks on it that start me on some sort of dialogue.”

In her essay in the January 2023 issue of “Evokation”, Mara Christian Harris recalls Post-it notes in Russell’s studio, one of which contained the phrase “Listen to the paint.” The phrase recalls Diebenkorn who wrote, “I don't go into the studio with the idea of 'saying' something. What I do is face the blank canvas and put a few arbitrary marks on it that start me on some sort of dialogue.”

In her essay, Elizabeth L. Delaney writes, “Russell maintains hands-on contact with her medium at every stage of the creative process, even making her own paint. When it’s time to work, she often begins painting directly on the canvas without any preliminary work. This approach preserves a sense of spontaneity, while also allowing the artist to explore her vision freely—or be led by the paint as she applies it. ‘You either tell the painting where it’s going, or it tells you,’ she says….

“Russell embraces the essential, timeless qualities of total abstraction contained within the formal elements from which she derives visual matter, even as she infuses her paintings with the deep, internal feeling that propelled her to pick up a paintbrush in the first place.”

As a vociferous advocate of contemporary representational art since the early 90s I curated 3 exhibitions of figurative art here at Evoke. One of the many great things about the gallery, however, is its mix of representation and abstraction.

As a vociferous advocate of contemporary representational art since the early 90s I curated 3 exhibitions of figurative art here at Evoke. One of the many great things about the gallery, however, is its mix of representation and abstraction.

Diebenkorn wrote, “All paintings start out of a mood, out of a relationship with things or people, out of a complete visual impression. To call this expression abstract seems to me often to confuse the issue. Abstract means literally to draw from or separate. In this sense every artist is abstract . . . a realistic or non-objective approach makes no difference. The result is what counts.”