Looking & Seeing

one long look at one work of art

John O'Hern is an arts writer, curator and retired museum director who is providing a weekly contemplation of a single work of art from our gallery. In our fast-paced lives overflowing with information, we find it necessary and satisfying to slow down and take time to look. We hope you enjoy this perspective from John.

John O'Hern has been a writer for the 5 magazines of International Artist Publishing for nearly 20 years. He retired from a 35-year-long career in museum management and curation which began at the Albright-Knox Art Gallery where he was in charge of publications and public relations and concluded at the Arnot Art Museum where he was executive director and curator. At the Arnot Art Museum he curated the groundbreaking biennial exhibitions Re-presenting Representation. John was chair of the Visual Artists Panel of the New York State Council on the Arts and has written essays for international galleries and museums.

February 9, 2025

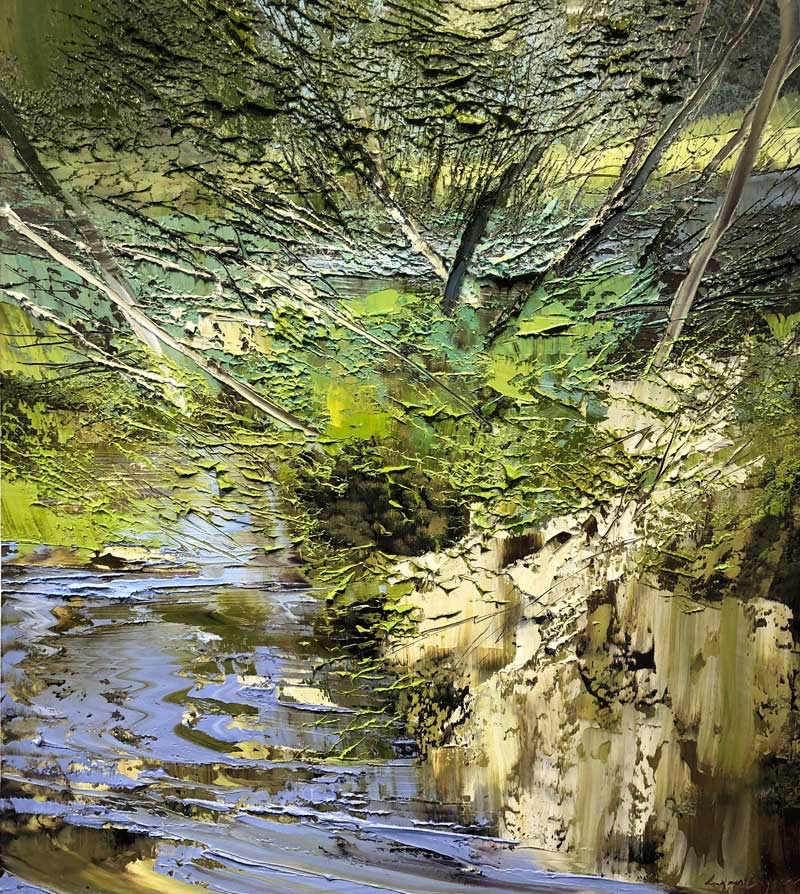

Lynn Boggess | 16 June 2023

Lynn Boggess and Andrew Wyeth grew up in East Coast farmland, Lynn in West Virginia and Wyeth in Pennsylvania and Maine. “When I saw his work,” Lynn says, “I related to it directly.”

He was introduced to Wyeth’s watercolors by an enthusiastic junior high school art teacher. “His quick study watercolors were a huge influence,” Lynn explains.

“I like abstract expressionism,” he continues, “which is why I related to his watercolors. His egg tempera paintings show masterful control but I find them way too tight.”

Only a few of Wyeth’s abstract watercolors were available to the public during his lifetime, but in 20023/24, the Brandywine Museum of Art showed over 70 works from Andrew and Betsy Wyeth’s private collection in the exhibition Abstract Flash: Unseen Andrew Wyeth.

Wyeth had written, “My struggle is to preserve that abstract flash – like something you caught out of the corner of your eye, but in the picture you can look at it directly.”

Elsewhere he wrote, “With watercolor, you can pick up the atmosphere, the temperature, the sound of snow shifting through the trees or over the ice of a small pond or against a windowpane. Watercolor perfectly expresses the free side of my nature . . . The brain must not interfere. You’re painting so constantly that your brain disappears, and your subconscious goes into your fingers and it just flows.”

His comments might have been made by Lynn who, although he paints with oil, has a keen sense of composition and often enters a meditative state as he gazes at the landscape and creates his paintings.

He has said, “Landscape paintings are philosophies encased in compositions. This really is a very complex, critical question. I avoid using the Golden Section and prefer focal points either in the middle or on the edges because they allow the space to be read simultaneously as a flat abstraction and as a recessional depth–something that helps me understand the paradoxes of life in general. That paradoxical experience is also emphasized in the illusion of space and the thick texture of the paint.”

He has said, “Landscape paintings are philosophies encased in compositions. This really is a very complex, critical question. I avoid using the Golden Section and prefer focal points either in the middle or on the edges because they allow the space to be read simultaneously as a flat abstraction and as a recessional depth–something that helps me understand the paradoxes of life in general. That paradoxical experience is also emphasized in the illusion of space and the thick texture of the paint.”

If the unlikely passerby could see Lynn painting at his unlikely sites, they would see him paint with a trowel on large canvases mounted on a portable studio he has carted into the wild, standing on its wood floor under its canopy. His wife, Jennifer, has written about his choice of sites. “Being on site gave him a certain empathy with the land. Subjects that he found most fascinating were those in which there was evidence of a struggle. He was drawn to broken trees, wind-swept rubble, great boulders, and flood water. That connection remains in his mature work, which is heroic in its subject and process. As the paintings have become larger, the discipline of being present continues. An assembly of easels, boxes, and scaffolds is necessary to bring the canvas to the subject. The work is created in all kinds of weather and on all types of terrain.”

This week’s Looking and Seeing painting is his 16 June 2023, capturing a moment in time. I chose it from the many other paintings that attracted me because it had water, rocks and vegetation. His other paintings have water, rocks and vegetation but this had a certain, what I hesitate to call a certain je ne sais quoi depicting a not particularly “photogenic” scene.

This week’s Looking and Seeing painting is his 16 June 2023, capturing a moment in time. I chose it from the many other paintings that attracted me because it had water, rocks and vegetation. His other paintings have water, rocks and vegetation but this had a certain, what I hesitate to call a certain je ne sais quoi depicting a not particularly “photogenic” scene.

Lynn, of course, knew what the “quoi” was that attracted him. “I want to see a scene that has something to say,” he explains--rock and water, contrast. The trees create an infinite space. I’Il get into the trees and set up my little meditative shelter. I meditate on what is transpiring in front of me, the movement in the water, the solid rocks and trees. You need both.”

Water and rock are adversaries even deep in the West Virginia woods. We’re familiar with the ocean crashing against the rocky shore, but their adversarial relationship also takes place in quieter ways. Water seeps into cracks in the rocks and, when it freezes, breaks the rocks apart, continuing their gradual erosion which creates soil in the which the trees and plants can grow.

Echoing Wyeth’s abstract flash caught out of the corner of his eye that he could paint so the viewer would see it directly, Lynn often avoids the centrality of the Golden Section, as he says, and allows the eye to travel around the composition.

Echoing Wyeth’s abstract flash caught out of the corner of his eye that he could paint so the viewer would see it directly, Lynn often avoids the centrality of the Golden Section, as he says, and allows the eye to travel around the composition.

His thick impasto of oil paint is applied with a trowel. Although I marvel at the awesome detail and subtle luminosity of nearly photographic realism, I love paint—it’s lush viscosity, it’s having its own mind.

“I was still into the discipline of painting at the time and discovered the playfulness and chaos of moving the paint around. When I accessed this textural thing, it was the freedom I was looking for. Painting wet on wet is half accident, and I learned by trial and error. It’s a hard way to learn but you never forget it. You don’t know exactly what’s going to happen but you kind of know within a bracket.

“What I try to get are areas of quiet, and areas of increased activity building up to a crescendo—not just one emotion. I start off in high gear and at the very end of the experience I slow and resolve awkward areas, sometimes back in the studio.

The thick paint and trowel gestures give the paintings a multidimensional quality. “The thickness of paint functions as much as hue,” he says, “Lit correctly, the paint functions as a relief sculpture.”

I was attracted by the water in 16 June 2023, its movement and reflections as well as the dimensionality and dimensionless qualities of its ripples. Rising up from the water are planar rocks and a cacophony of trees, branches, leaves and gradations of light.

I was attracted by the water in 16 June 2023, its movement and reflections as well as the dimensionality and dimensionless qualities of its ripples. Rising up from the water are planar rocks and a cacophony of trees, branches, leaves and gradations of light.

He explains, “I’m trying to document an experience. I’m not just doing images. I could do that sitting at home with an iPad. I do realism, not naturalism. Realism adds an emotional element. All those forms are in flux and I don’t paint exactly what I’m looking at. If I sat in the studio I would become idealistic. I have to have the tactile grittiness of nature. I try to understand it and give it something of myself and what I think.

“You can’t just go out and expect nature to speak to you. It’s not going to happen. You have to engage with nature, meet it in the middle.”