Looking & Seeing

one long look at one work of art

John O'Hern is an arts writer, curator and retired museum director who is providing a weekly contemplation of a single work of art from our gallery. In our fast-paced lives overflowing with information, we find it necessary and satisfying to slow down and take time to look. We hope you enjoy this perspective from John.

John O'Hern has been a writer for the 5 magazines of International Artist Publishing for nearly 20 years. He retired from a 35-year-long career in museum management and curation which began at the Albright-Knox Art Gallery where he was in charge of publications and public relations and concluded at the Arnot Art Museum where he was executive director and curator. At the Arnot Art Museum he curated the groundbreaking biennial exhibitions Re-presenting Representation. John was chair of the Visual Artists Panel of the New York State Council on the Arts and has written essays for international galleries and museums.

December 15, 2024

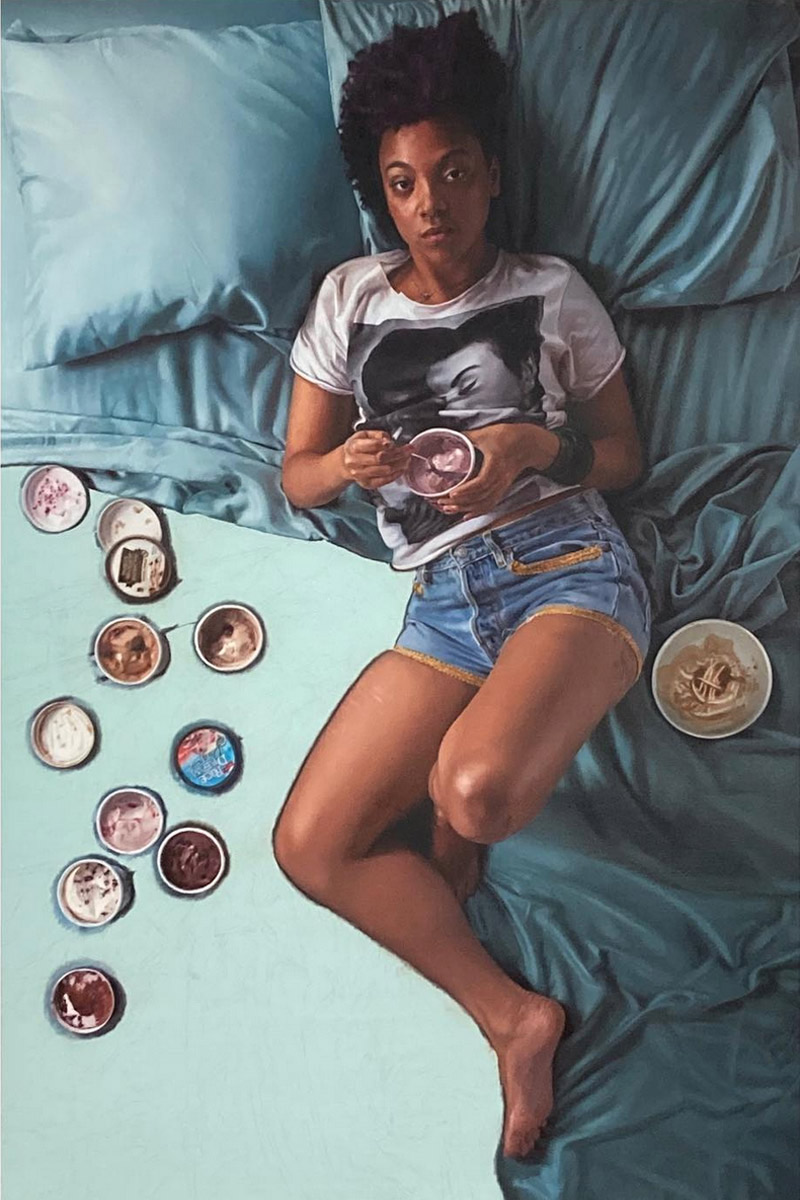

LEE PRICE | Nicole

From time to time when I was a museum director and parents would recommend the art of their children or that of other relatives, I would hit the jackpot. One of those times was in 2004 when Emilie Price told me her daughter Lee had submitted paintings to be judged into the Regional Exhibition at the Arnot Art Museum in Elmira, NY. Lee won Best Work in Oil that year for her small painting of a piece of gold damask with its tightly-painted shimmering highlights and soft shadows. She won another important prize the following year. I knew she was someone to follow but lost track of her when I left the museum and moved to Santa Fe.

But not for long. I moved to Santa Fe in 2007 and Evoke began representing Lee in 2010 just as I was preparing the first of three exhibitions I curated for the gallery. No longer producing intimate paintings of fabric, she had begun painting her Women and Food series in 2007 with the painting Full, a 44 by 54” canvas. She had been painting images of women in rooms with a nebulous relationship to the food they held or happened to be nearby. In Women and Food the relationship became more specific.

“Growing up,” Lee writes, “I lived with my mother and my two older sisters. In our household, women did everything. There were no men's roles because there were no men around. My father had left and, though he continued to live in the same town we did, was not a consistent presence in my life. Both grandfathers had passed away before I was born. No other male relatives lived nearby. I attended an all women’s college. All this has shaped my view of the world.”

“I was 2 or 3 paintings into the series before I realized the subject was me and my compulsive eating disorder which, at the moment, I’m pretty much over. Once I realized it, I was able to continue and then it morphed into different themes over the years.”

The view from above in her paintings is neither voyeuristic nor judgmental. It is her watching herself and, in the instance of Nicole, the subject looking at herself, not as an object, but as a women caught in an obsession and daring anyone to comment on it. “When you’re doing something compulsive,” Lee says, “you can’t stop yourself. You’re watching yourself do it. It’s an out of body experience where you’re watching yourself as if you’re somebody else.”

In an interview with Brianna Lyle of “Flatt” magazine, Lee said, “The majority of my pieces are speaking about checking out; food as a means of distracting yourself from being present. The settings are always peaceful behind the frenetic activity of the subject. These women are searching for solace in an unfit source. The peace is there. It’s obvious. It’s just underneath the behavior. This is how compulsion is. My paintings explore the ways in which we take comfort in food and its pleasures, and the hunger that remains even amidst apparent abundance. Sometimes I’m simply speaking about the search for the lusciousness of life.”

Often, the women (she) have chosen the bathtub or the bathroom floor to indulge. “The private space,” she explains, “emphasizes the secrecy of compulsive behavior and the unusual settings emphasize its absurdity. The solitude/peace of the setting is a good juxtaposition to the frenetic, out-of-control feel of the woman’s actions.”

Nicole is based on a photograph from over 10 years ago. Lee’s paintings are derived from 100s of photographs taken of her carefully choreographed setups often over the course of a entire day. The model is primarily herself, but Nicole contacted Lee on the Internet and asked if she could model.

Nicole is based on a photograph from over 10 years ago. Lee’s paintings are derived from 100s of photographs taken of her carefully choreographed setups often over the course of a entire day. The model is primarily herself, but Nicole contacted Lee on the Internet and asked if she could model.

Sometimes, Lee’s look is meditative or inward looking. At other times she gazes directly at the viewer but is lost in her own state of being. Nicole, on the other hand, presents herself as defiant. “It’s her expressing herself,” Lee comments.

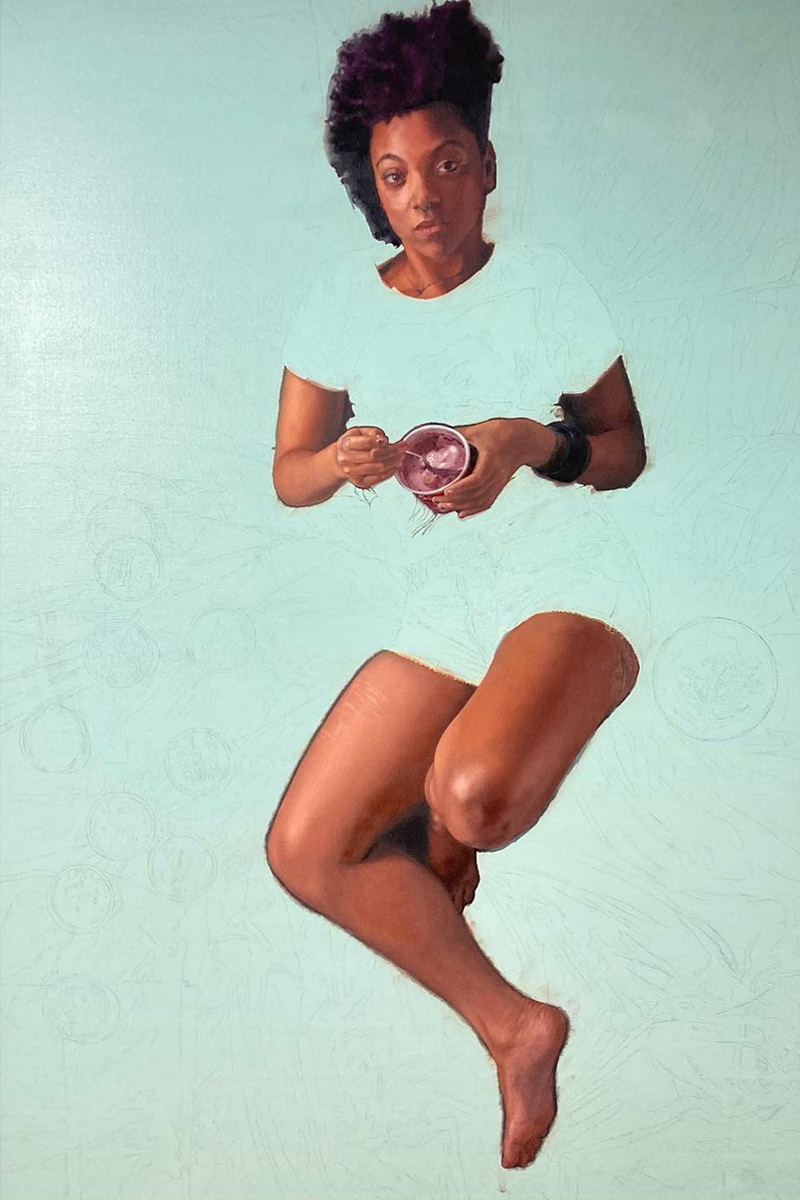

On her Instagram page, Lee has posted the painting of Nicole in progress. “When I paint,” she says, “I go object by object. Sometimes I tackle the figure first. I do the easier stuff after that. I’m definitely not somebody who’s a super lover of the process, though. Sometimes it can be tedious. Right now I’m going full speed preparing for my exhibition, Cake, that will be at Evoke in April. I’m hoping to have 9 new paintings.”

On her Instagram page, Lee has posted the painting of Nicole in progress. “When I paint,” she says, “I go object by object. Sometimes I tackle the figure first. I do the easier stuff after that. I’m definitely not somebody who’s a super lover of the process, though. Sometimes it can be tedious. Right now I’m going full speed preparing for my exhibition, Cake, that will be at Evoke in April. I’m hoping to have 9 new paintings.”

Lee has always been drawn to realism. She says, “Everyone’s either a Vermeer or a Sargent. You can never be the other one. I’m a Vermeer who always wanted to be a Sargent with his gestural brush strokes and soft edges. I have to embrace my Vermeerness.”

She graduated from Moore College of Art in with a BFA in Painting, cum laude. She has studied privately with Alyssa Monks and with Alyssa and Dan Thompson at New York Academy of Art. More recently she has been studying with Christopher Gallego.

“I’ve studied with Alyssa for years,” she relates. “She taught me how to paint the way I paint and about the technical aspects of how I make my paintings. Prior to her, I don’t know if I got anything technical from anyone.

“I’m drawn to studying with Chris. He’s taught me about blending and edges and has me wanting to begin to paint from life. What I get from him is enjoyment.”

In her “Artist’s Statement”, she writes of the consequences of obsession. “One of the most potent messages these pieces deliver is that of excessive waste. Not just material waste but the waste of time and energy that is used up in obsession. Energy that could be directed towards productive endeavors, through our compulsive activity, is instead being used to wrap us in a cocoon. Where we could be walking forward, we instead paralyze ourselves. For the women in these paintings, even with an excess of food, there is no nourishment. Unable to sit with the discomfort/unease of the present moment, these women take in excessive amounts and in the process are shutting out the possibility of being truly nourished.”

In her “Artist’s Statement”, she writes of the consequences of obsession. “One of the most potent messages these pieces deliver is that of excessive waste. Not just material waste but the waste of time and energy that is used up in obsession. Energy that could be directed towards productive endeavors, through our compulsive activity, is instead being used to wrap us in a cocoon. Where we could be walking forward, we instead paralyze ourselves. For the women in these paintings, even with an excess of food, there is no nourishment. Unable to sit with the discomfort/unease of the present moment, these women take in excessive amounts and in the process are shutting out the possibility of being truly nourished.”