Looking & Seeing

one long look at one work of art

John O'Hern is an arts writer, curator and retired museum director who is providing a weekly contemplation of a single work of art from our gallery. In our fast-paced lives overflowing with information, we find it necessary and satisfying to slow down and take time to look. We hope you enjoy this perspective from John.

John O'Hern has been a writer for the 5 magazines of International Artist Publishing for nearly 20 years. He retired from a 35-year-long career in museum management and curation which began at the Albright-Knox Art Gallery where he was in charge of publications and public relations and concluded at the Arnot Art Museum where he was executive director and curator. At the Arnot Art Museum he curated the groundbreaking biennial exhibitions Re-presenting Representation. John was chair of the Visual Artists Panel of the New York State Council on the Arts and has written essays for international galleries and museums.

October 20, 2024

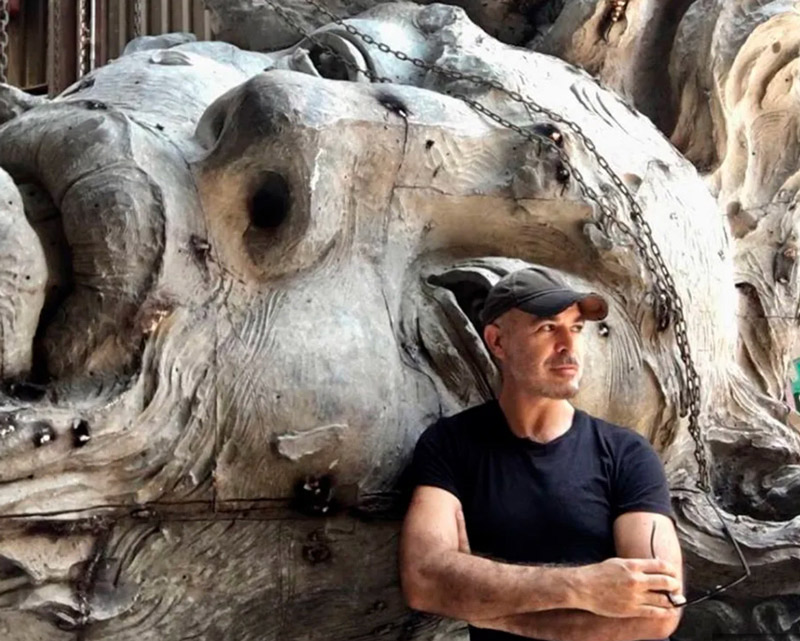

JAVIER MARÍN | Cabeza Hombre II

In 1996/97, I included Por Ti, a ¾-length, 67-inch, male nude clay sculpture by Javier Marín in the exhibition Re-presenting Representation III at the Arnot Art Museum. It arrived in several sections which we carefully stacked one on top of the other. When I asked the lender, who lived in Los Angeles, what he did in an earthquake he said, “We run and hold on to it!” It commanded the two-story gallery.

In 2001, I included a large clay Cabeza with Medusa-like hair in the exhibition Re-presenting Representation at the Corning Gallery downstairs from the Steuben showroom on Madison Avenue in Manhattan. We installed it in front of a wall we had painted Pompeiian Red at the bottom of the flight of glass stairs. It looked spectacular.

Both pieces were in clay from Oaxaca and Zacatecas--traditional, precolonial sources. The clays and clay slips gave each piece a richly mottled warm orange and red color. The permanently assembled parts of Por Ti were held together by metal staples. The sculpture came with a box of staples which we placed in their corresponding holes once we had stacked the sections.

I was attracted by the passion of the sculptures—in the pose and facial expression of Por Ti and in the ferocious intensity of the Cabeza. But Marín’s intense modeling of the clay was equally captivating. Since the figures were fired clay, I knew that he had moved his tools right there and there’s where he moved the clay around with his fingers.

Passion was on my mind, it seems, when I wrote the text for the Arnot catalogue. “Preconceptions of the Latin temperament and unbridled passion confront the viewer of the sculpture of Javier Marín. Teresa del Conde, director of the Museo de Arte Moderno in Mexico City, has written of Marín’s work: ‘Most of the sculptures seem to be affected by psychomachia—that is, they suggest a battle between good, seen as pleasure, and evil, seen as suffering. Pleasure is sensual and in many cases, sexual, even orgiastic. It is accompanied though by the warning of the finiteness of such pleasure and of a concomitant suffering.’ If the viewer’s preconception is that pleasure is evil and suffering, good, another level of interpretation or a mental shutdown occurs. Modeled traditionally in clay, the sculptures are assembled as fragments, the fragments themselves combining to create only the fragment of a figure. They remind the viewer of the modeling of man from clay by the biblical god, the fragmentation brought about by The Fall, and the captivating attraction to the erotic, dark unknown we find in the works of Gabriel García Márquez.”

Passion was on my mind, it seems, when I wrote the text for the Arnot catalogue. “Preconceptions of the Latin temperament and unbridled passion confront the viewer of the sculpture of Javier Marín. Teresa del Conde, director of the Museo de Arte Moderno in Mexico City, has written of Marín’s work: ‘Most of the sculptures seem to be affected by psychomachia—that is, they suggest a battle between good, seen as pleasure, and evil, seen as suffering. Pleasure is sensual and in many cases, sexual, even orgiastic. It is accompanied though by the warning of the finiteness of such pleasure and of a concomitant suffering.’ If the viewer’s preconception is that pleasure is evil and suffering, good, another level of interpretation or a mental shutdown occurs. Modeled traditionally in clay, the sculptures are assembled as fragments, the fragments themselves combining to create only the fragment of a figure. They remind the viewer of the modeling of man from clay by the biblical god, the fragmentation brought about by The Fall, and the captivating attraction to the erotic, dark unknown we find in the works of Gabriel García Márquez.”

As I wander into octogenarianhood I’m reminded of a different observation by Márquez: “It is not true that people stop pursuing dreams because they grow old, they grow old because they stop pursuing dreams.”

Marín was 34 when I first showed his work. He has since gone on to cast his clay sculptures in bronze and polyester resin as well as to produce multi-colored sculptures by polymer 3D printing. The quality of his casts, fortunately, captures the immediacy of his mark making in clay.

Some years ago, when Evoke was being born at its Lincoln Avenue location, I stopped in to say “Hi” to Kathrine. She brought out a catalogue of Marín’s sculptures and asked, “Do you know this artist?” I replied in my characteristically understated way, “JAVIER MARÍN?!” I knew then that she and I were on the same wavelength. Scary, but true.

Some years ago, when Evoke was being born at its Lincoln Avenue location, I stopped in to say “Hi” to Kathrine. She brought out a catalogue of Marín’s sculptures and asked, “Do you know this artist?” I replied in my characteristically understated way, “JAVIER MARÍN?!” I knew then that she and I were on the same wavelength. Scary, but true.

Since then, a number of his gorgeous bronze and resin sculptures have been shown at the gallery. The bronze sculpture, Cabeza Hombre II, is now on view and is an example of the passion and immediacy I admired in his clay sculptures nearly 30 years ago despite its comparatively diminutive size.

The passionate art of the Baroque period broke from the almost impossible ideals and beauty of the Renaissance.

Cabeza Hombre II embodies that passion and the beauty of the not-ideal. We see the intense emotion in the downcast eyes, the expressive lips and the twist of the body of this hombre. We see into him through holes in his chest and the back of his head. The artist’s passion is visible in the marks and movements of his modeling. Just as the clay in the early pieces is expressive of itself in its color variations, the bronze is reused, “made out of all the junk you can imagine,” he says. “The result is a bronze with a very stained skin, really dirty… I want to respect that, if it’s stained it’s for some reason. Plus, it is very beautiful.”

Cabeza Hombre II embodies that passion and the beauty of the not-ideal. We see the intense emotion in the downcast eyes, the expressive lips and the twist of the body of this hombre. We see into him through holes in his chest and the back of his head. The artist’s passion is visible in the marks and movements of his modeling. Just as the clay in the early pieces is expressive of itself in its color variations, the bronze is reused, “made out of all the junk you can imagine,” he says. “The result is a bronze with a very stained skin, really dirty… I want to respect that, if it’s stained it’s for some reason. Plus, it is very beautiful.”

The piece makes us aware of the process of its making, a process that reflects our own making and our remaking as well as our pursuing our dreams.

Marín has widely broadened his scope since I first showed his work in 1996. My favorite is the spectacular Retablo, the composition-winning multi-figure altarpiece for, appropriately, the Cathedral Basilica of Zacatecas, Mexico.

Marín has widely broadened his scope since I first showed his work in 1996. My favorite is the spectacular Retablo, the composition-winning multi-figure altarpiece for, appropriately, the Cathedral Basilica of Zacatecas, Mexico.

In 2013 he created the Fundación Javier Marín. The foundation states, “We harness the creative nature of human beings as a tool for social development. We build programs that support the professionalization of artists, artisans, designers and different actors involved in cultural activity.”