Looking & Seeing

one long look at one work of art

John O'Hern is an arts writer, curator and retired museum director who is providing a weekly contemplation of a single work of art from our gallery. In our fast-paced lives overflowing with information, we find it necessary and satisfying to slow down and take time to look. We hope you enjoy this perspective from John.

John O'Hern has been a writer for the 5 magazines of International Artist Publishing for nearly 20 years. He retired from a 35-year-long career in museum management and curation which began at the Albright-Knox Art Gallery where he was in charge of publications and public relations and concluded at the Arnot Art Museum where he was executive director and curator. At the Arnot Art Museum he curated the groundbreaking biennial exhibitions Re-presenting Representation. John was chair of the Visual Artists Panel of the New York State Council on the Arts and has written essays for international galleries and museums.

September 29, 2024

FRANCIS DIFRONZO | Crossing Paths, Part 2

When Francis DiFronzo was a beginning art student at California State University, Fullerton, he finished his drawing quickly in a life drawing class and went outside for a smoke. His teacher, who felt he was talented but not really applying himself, stopped him and said, “If you’re done, change your position and do a second drawing.” By the end of the semester,he admits, “I was more competent at drawing the figure. My teacher told me that he wished he could lock me in the desert for a year to see what I could do without distractions. A couple of years later I felt under pressure to find my own voice. I thought maybe I should go to the desert. I was too influenced by other artists and my teachers.

“I went to Bell Mountain near Victorville in the Mojave Desert. I found a house that had been turned into a duplex and half was for rent. It was super cheap--2 rooms and a bathroom. After 8 or 9 weeks I didn’t know what to draw or what to paint. There was no radio and it was a 30 minute drive to the nearest phone. I was 21 and knew I was not ready to be on my own all the time.

“Interestingly, last year I purchased a negative to digital converter. I did take photos in the desert. When I converted them I was afraid to look at them at first.”

There were visual and spiritual experiences, however. “I remember sitting at the front door of my house, at sunset” he recalls. “I was looking toward the east rather than at the setting sun. It was the nicest experience, how the Belt of Venus appeared in the sky above the shadow of the earth. Night rises as the sun sets.” Explaining the Belt of Venus, the BBC states, “To properly see the Belt of Venus, all you need is a clear sky, shortly before sunrise or after sunset, and an unobstructed horizon.” Francis had unobstructed horizon in abundance to observe the pink band named after the Greek goddess of love and beauty and the girdle she wore that had the power to inspire passion. His “nicest experience” was the beginning of his passion for the desert.

He left the desert and attended graduate school at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. He found he was still trying to find his voice and, later, decided to return to the desert. “I wanted to shake myself up. I wanted to spark something. I said, ‘You’re not who you were back then.’ When I arrived in Bell Mountain, the house was gone. There was a pile of wood where the house had been and a clean concrete slab. That ended up to be the impetus to move on.”

And move on, he did. He has always admired the work of Andrew Wyeth and Edward Hopper and says, “I want to portray the desert with the same passion and attention to detail as the east coast artists did with their environment. In simple tonal paintings, I want to portray how I feel about the southwest and the timelessness of nature—nature as continuum.” The fading signs and rusting box cars in his paintings may outlive us and the concrete slab of his home in the desert will undoubtedly outlive human life on the planet.

Along the way, he was awarded a Stobart Foundation Fellowship in the Arts as well as a Pew Fellowship in the arts. In 2015, 5 of his paintings were featured in the second season of the award-winning television series “Better Call Saul”.

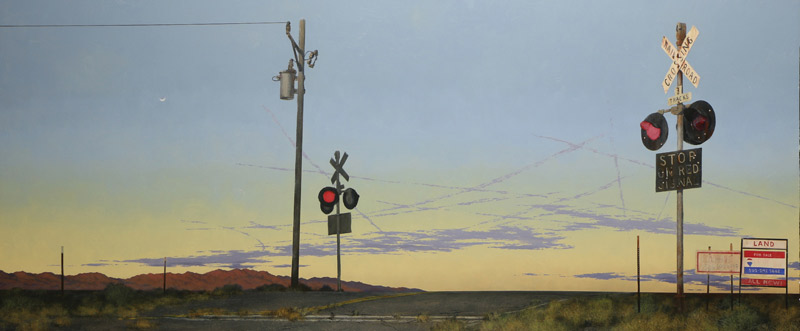

Among his paintings at Evoke is Crossing Paths, Part 2. A summation of many of his experiences imagined into a cohesive composition that invites the viewer’s exploration and response. He says, “I think the thing that makes good art is a sense of mystery. I like being a little opaque. I draw people into my world and give enough information so they know there’s a meaning.”

Among his paintings at Evoke is Crossing Paths, Part 2. A summation of many of his experiences imagined into a cohesive composition that invites the viewer’s exploration and response. He says, “I think the thing that makes good art is a sense of mystery. I like being a little opaque. I draw people into my world and give enough information so they know there’s a meaning.”

On the far right of the 5-foot panel are faded signs for real estate, symbolic of failed dreams. One still legible sign bears an active phone number.

“In general, he explains, “the Crossing Paths paintings are about transportation, the mark that humankind leaves everywhere, like the concrete slab of my house in the Mojave. Worlds cross, airplane contrails cross in the sky. And there are unseen crossed paths. The thought or premise is how human lives interact, how lives cross paths. In , I wanted to give some sort of reference to my own life, how opportunity comes and goes. Call that phone number.”

The railroad crossing signs are self-explanatory and are a fortuitous link to an art installation just down the street from the gallery at the New Mexico Museum of Art Vladem Contemporary. Last year, the museum’s first artist in residence, Colombian artist Oswaldo Maciá. created a sound sculpture installation, El Cruce—“cross” or “crossing” and all its meanings. He incorporates the sounds of crossing from migratory bats and the sounds of wind in the desert to the sounds of the railyard just below the sculpture terrace where his piece is installed.

The railroad crossing signs are self-explanatory and are a fortuitous link to an art installation just down the street from the gallery at the New Mexico Museum of Art Vladem Contemporary. Last year, the museum’s first artist in residence, Colombian artist Oswaldo Maciá. created a sound sculpture installation, El Cruce—“cross” or “crossing” and all its meanings. He incorporates the sounds of crossing from migratory bats and the sounds of wind in the desert to the sounds of the railyard just below the sculpture terrace where his piece is installed.

In an essay I wrote for the museum, I refer to crossing. “Today, it continues to refer to intersections but also to transitions (‘crossing over’, ‘crossing borders’) and, in the case of sculpture, ‘crossing the limits of perception’. Maciá refers to the migration of the Spanish and colonists to Santa Fe and the migration of artists drawn by the desert and its extraordinary light. He refers, as well, to present day migrants crossing through Central America to our southern border.”

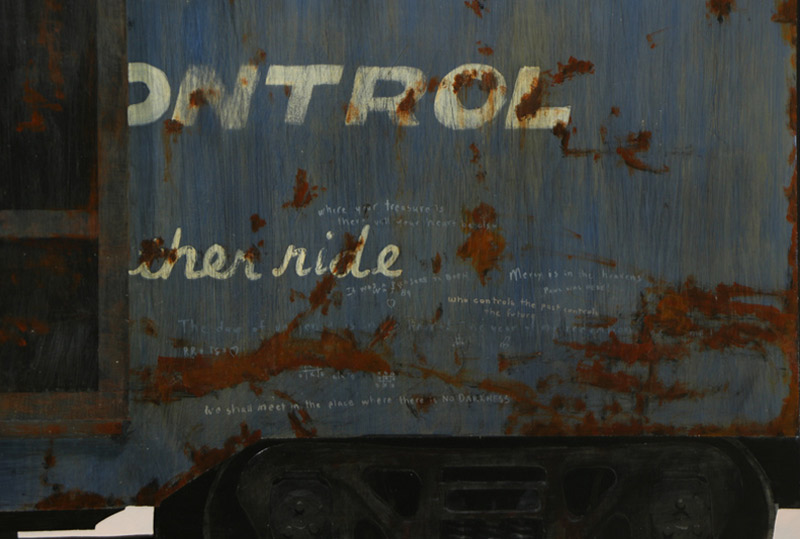

People have come and gone from the desert of the southwest. Among the photos Francis took when he first lived in the desert were several of a long-abandoned church. Painted on a rafter was a passage from Genesis—“Why are you distressed, and why is your face fallen”—words God spoke to Cain after he accepted Abel’s offering and rejected Cain’s.

Francis incorporated the quote in his painting, The Cathedral. “I often imagined what those words would mean to a child,” he explains. “There’s no reason God favored Abel. As a child myself, I loved the sense of community, of a family coming together. In this painting I was thinking about how in the old days, religious people used to travel and spread the Word in cars and wagons and would open a temporary church.

Francis incorporated the quote in his painting, The Cathedral. “I often imagined what those words would mean to a child,” he explains. “There’s no reason God favored Abel. As a child myself, I loved the sense of community, of a family coming together. In this painting I was thinking about how in the old days, religious people used to travel and spread the Word in cars and wagons and would open a temporary church.

“I had envisioned people who had gathered together inside the cathedral, the younger generation writing on the side of the box car the things they heard inside, repeating what they learned. In the tic tac toe games, they make the same mistakes over and over again. We should learn from our mistakes.”

“I had envisioned people who had gathered together inside the cathedral, the younger generation writing on the side of the box car the things they heard inside, repeating what they learned. In the tic tac toe games, they make the same mistakes over and over again. We should learn from our mistakes.”

Francis is now teaching drawing and painting at California State University, Fullerton. David Hockney wrote, “Well you can't teach the poetry, but you can teach the craft.” Francis teaches the craft from stretching canvas to understanding chroma. “I also introduce them to pathways they can use to tap into their creative impulses. They have to find their own way. You learn it from yourself.”