Looking & Seeing

one long look at one work of art

John O'Hern is an arts writer, curator and retired museum director who is providing a weekly contemplation of a single work of art from our gallery. In our fast-paced lives overflowing with information, we find it necessary and satisfying to slow down and take time to look. We hope you enjoy this perspective from John.

John O'Hern has been a writer for the 5 magazines of International Artist Publishing for nearly 20 years. He retired from a 35-year-long career in museum management and curation which began at the Albright-Knox Art Gallery where he was in charge of publications and public relations and concluded at the Arnot Art Museum where he was executive director and curator. At the Arnot Art Museum he curated the groundbreaking biennial exhibitions Re-presenting Representation. John was chair of the Visual Artists Panel of the New York State Council on the Arts and has written essays for international galleries and museums.

December 8, 2024

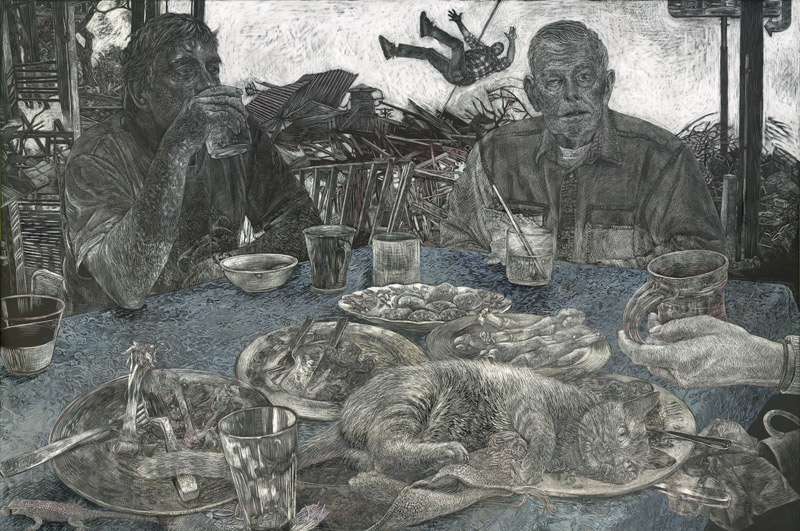

ALICE LEORA BRIGGS | Fall

Poet Laureate and Pulitzer Prize winner Mark Strand wrote, “We’re only here for a short while. And I think it’s such a lucky accident, having been born, that we’re almost obliged to pay attention.”

When I first met Alice Leora Briggs in 2014, she was working on a series of woodcuts inspired by Strand’s poem The Room. She told him that she loved the poem but she didn’t understand it. He replied, “Love comes first and understanding later.” Her interpretations of each line of the poem were inspired by the line itself, her family history and her experiences in Ciudad Juárez, Mexico. Strand died later in 2014 and the suite was published in 2016.

She had witnessed the unimaginable horror of the murders in Juárez in the company of the journalist Charles Bowden. The murders there, during the term of Mexican president Felipe Calderón, were practically ignored by the rest of the world. She and Bowden collaborated on a book, Dreamland: The Way Out of Juárez, published in 2010. Her sgraffito drawings and Bowden’s nonfiction text brought the surreality of the murders to life. Bowden, winner of the Lannan Award for Nonfiction, died in 2014.

In 2022, she published Abecedario de Juárez: An Illustrated Lexicon, co-authored with the photographer Julián Cardona who had migrated to Juárez with his family when he was a boy. In 1995, he curated an exhibition, Nada que ver (Nothing to See), which showed the work of photojournalists who documented the daily violence, death, and poverty of life in Juárez. He was awarded the Cultural Freedom Prize from the Lannan Foundation in 2004 and died in 2020.

Alice comments, “I love collaborating and the energy and the heat that generates.” Strand and Bowden were older than she and Cardona was younger, yet death claims whom it will when it will.

Her work has “always been about confronting death. I do meditate about death on a daily basis. I’m now watching my 103-year-old mother die as she lives with dementia. Thinking about death isn’t a morbid activity. I wake up in the morning and my first thought is ‘My god I’m alive. I’ve got another shot at this.’”

Her shots have been on the mark. When she was a teenager she entered poster contests winning a drawing table, a television and a trip to Washington, DC, among other things. As an adult her prizes have been more substantial. She was named a Fulbright Scholar in 2011 and received a Guggenheim Fellowship in 2020.

Recently, she has “begun to excavate my personal history to see how it will unfurl into imagery.” One of the images is Fall, a scene at her family’s dinner table with her father and her middle brother as well as the hand of her daughter. Fall, she says, “is as much about living as it is about dying.”

Her saying that reminded me of Kahlil Gibran who wrote, “If you would indeed behold the spirit of death, open your heart wide unto the body of life. For life and death are one, even as the river and the sea are one.”

Fall is done in sgraffito. Alice explains simply, “I cut white marks into black surfaces with a knife.” And more fully, “Sgraffito fixes on two facets of my work, drawing and writing. The word comes from the Italian graffiare — to scratch. This in turn is derived from Ancient Greek, γράφειν, to cut into, to write.

“I work on panels that are coated with kaolin clay and acrylic medium (for binder), then over sprayed with India ink. My drawing tools are simple: x-acto knives, fiberglass pencils, steel wool, engraving tools, anything that will abrade the ink’s surface or cut into the white clay.”

Resting on a plate among the remnants of a family meal in Fall, is a contented cat. “A feral cat moved into our back yard in Texas and brought a half-grown kitten,” she explains. “The kitten went off and the mother cat got pregnant again. We couldn’t trap her but we took the kittens and put them in boxes and socialized them so they could be adopted. Meanwhile, she had another litter. One day I left the door to my studio open and she came in, cautiously. I was able to shut the door, we had her fixed and she’s lived with us for 7 years.”

In the lower left corner of the drawing is “Jolly Roger” a lizard who is fond of blueberries.

Behind her father and brother are the wreckage of ghost towns the family would visit when they lived in Idaho.

Beyond it all is a boy falling through space—her brother Thomas. “He was just coming of age at 15,” she relates. “He loved mountain climbing and architecture. He was vibrant, kind and sweet to me. He died in a fall in the Tetons.”

I had asked her about a quote in which she spoke of “the extreme limit of understanding”. Shortly after we spoke, she sent me an email to expand on the thought.

She wrote: “I was educated early in the fragility of life. When I was seven years old, the Tetons hurled my oldest brother into an abyss. Our neighbors fared worse. The father and son went fishing on a river that pulled them out of this world. Six months later, the U.S. Army’s experimental reactor exploded at the National Reactor Testing Station where my chemical engineer father worked. Three young men died. Whatever was left of them was sealed in lead coffins and shipped to faraway cemeteries. Our family had no words.

My father was among the 'site' workers who spent 5 minutes cleaning the area until their dosimeter badges maxed out. I remember lying in the snow around this time, making snow angels with some other kids in the neighborhood. One friend warned me not to eat the snow, ‘It will kill you.’

“Our family fell silent about these deaths for nearly six decades. I did not know where my brother was buried until I was 15 and finally worked up the nerve to ask my parents. Long before the first day I walked into Juárez, I forgave my penchant to comprehend and speak about la frontera, the extreme limit of understanding. But this phrase 'the extreme limit of understanding' does not refer solely to death...it includes the extensive menu of pain that we humans knowingly (and unknowingly) inflict on ourselves and one another, all the while turning a blind eye.”

Having talked with her and having read her email, I thought back to a print in her suite of works for Mark Strand’s The Room.

Having talked with her and having read her email, I thought back to a print in her suite of works for Mark Strand’s The Room.

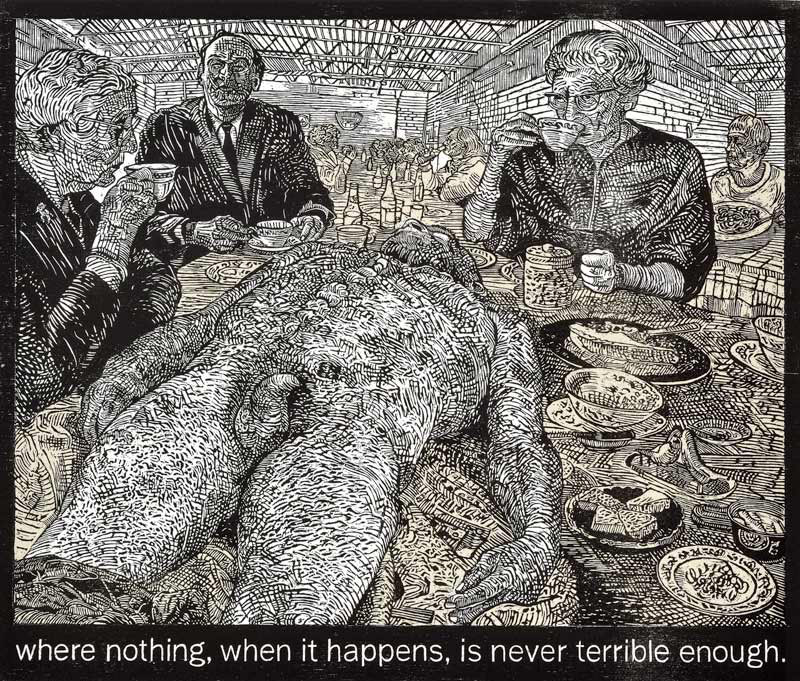

Ten years ago I wrote, “Line 12, Where nothing, when it happens, is never terrible enough was inspired by the line itself, her family history, her experiences in Ciudad Juárez, Mexico, and brings in Mantegna. Two genteel ladies and a gentleman sip tea oblivious to the party behind them and to the corpse lying on the table in front of them. The corpse recalls Mantegna and is taken from a photograph of a cadaver in a morgue in Juaréz following an execution and autopsy. It also recalls, for Briggs, the tragic mountain fall that took her brother’s life many years before.”

Alice brings life and death and art history into her work. The nude figure in this woodcut recalls the brilliantly foreshortened Lamentation Over the Dead Christ, ca. 1483 by Andrea Mantegna (ca. 1431-1506).

“I used to feel apologetic about my predilections,” she says, “but when I finally went to Europe (at the age of 42), I realized that I was in pretty good company, one more voice in a centuries-long tradition of Judeo-Christian visual narratives.”

Alice brings life and death and art history into her work. The nude figure in this woodcut recalls the brilliantly foreshortened Lamentation Over the Dead Christ, ca. 1483 by Andrea Mantegna (ca. 1431-1506).

“I used to feel apologetic about my predilections,” she says, “but when I finally went to Europe (at the age of 42), I realized that I was in pretty good company, one more voice in a centuries-long tradition of Judeo-Christian visual narratives.”